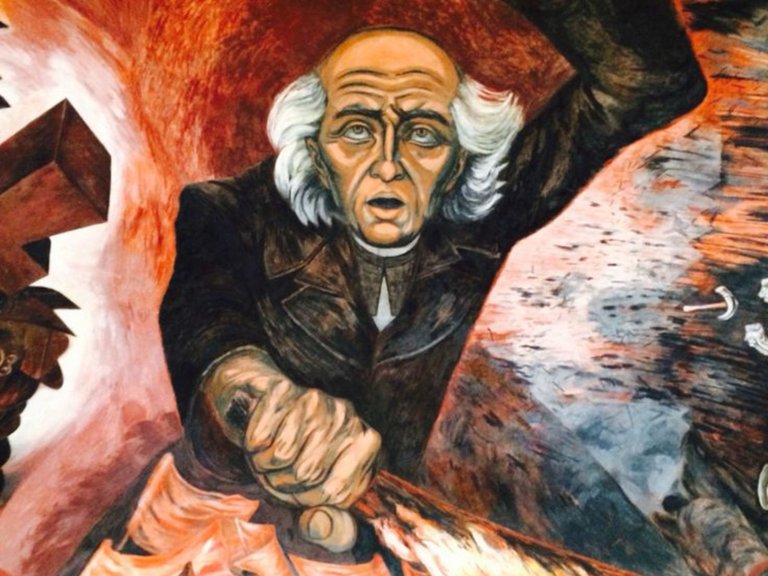

Miguel Hidalgo, the Priest who Ignited Mexican Indipendence

After publishing my post about the Angel of Independence, one of the replies I received from @city-of-berlin mentioned she would be interested in the statues at the foot of the column. You will remember that I could not get close to, as it is still cordoned of indefinitely, supposedly for renovation. Since then she has published a couple of posts about famous German leaders, such as Roon, Moltke, and Bismarck, so I did not want to feel left behind.

image source

Instead of waiting for the Angel Column to be renovated, I decided to visit other statues of the same people, starting with the most important one. After all, the leaders of the Mexican Independence, called Insurgents, are pretty much everywhere, all over this country, especially in the capital. And particularly the main guy happens to have my district named after him, so I didn't have to walk more than five minutes to the district's administrative center to find a large bronze statue of him.

Not Your Typical 18th Century Catholic Priest

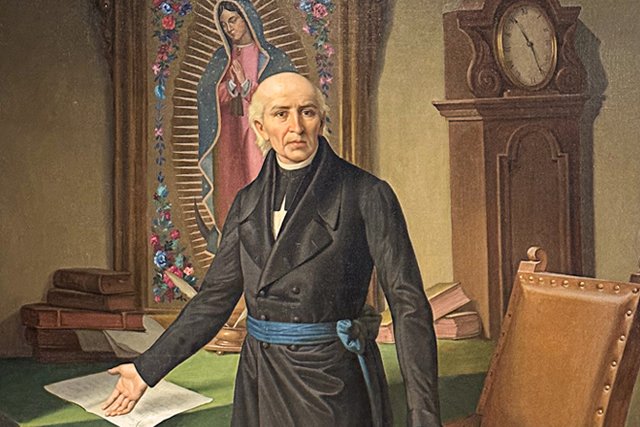

Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla Gallaga Mandarte y Villaseñor is the illustrious name of the man given most credit for starting the struggle for independence, though most people today know him as simply Miguel Hidalgo.

Hidalgo was born in 1753 into a Criollo family, meaning that his ancestry was 100% pure European, with the slight blemish that, just like his parents, he was born on the American continent. This seemingly minor detail became a major disadvantage compared to European-born Spaniards, and resulted in being one of the contentious points causing the war for independence.

image source

Like many other Criollos, Hidalgo's family were of decent means, and even in his own life he accumulated no less than three haciendas. Being intellectually inclined, Miguel Hidalgo studied at the Colegio San Nicolas in Morelia (back then Valladolid) to enter the priesthood in 1778. The new and seemingly radical ideas of the enlightenment had a profound effect on him, which however also got him in trouble with the church authorities. Having fallen out of favor for his progressive teaching style, he became a parish priest, first in Colima, later in Dolores, in the modern state of Hidalgo, named after him.

In spite of being disliked by the church power, Hidalgo was left to his own devices sufficiently to practice a lifestyle that was in strong contradiction to being a catholic priest. Disregarding his vow of celibacy, he had at least four female partners in his life, with whom he fathered at least eight children. Also, for being a Criollo, Hidalgo systematically ignored racial boundaries, hosting in his home guests of all backgrounds, whether they were Indios, Mestizos, Criollos, or Spanish. However, he was far from being merely a welcoming host to people from all walks of life. In his parish he did a lot to improve the economic and labor conditions of the local populace, for example by establishing leather and clay working manufactures, and promoting the cultivation of grapes and olives, two crops that had been forbidden from being grown in the New World in order to keep out of competition with Spain.

The Querétaro Conspiracy and the Cry of Dolores

Among the friends who came to visit Hidalgo were like minded Criollos, who were tired of being discriminated by European-born Spaniards. Their dissatisfaction saw a potential for change when the Spanish royalty - and thus the viceroyalty in the New Spain - was suddenly reshuffled after Napoleon marched into Spain and put his brother on the throne. This was the chance for Mexican-born Spaniards to take matter into their own hands.

The conspiracy to overthrow the colonial government was organized in the town of Querétaro, where the most influential criollos in both civilian and military life met in secret at the home of the mayor Miguel Dominguez and his wife Josefa Ortiz. Among the most notable conspirators were Ignacio Allende, Mariano Abasolo, Juan Aldama, and of course Hidalgo himself. Today they are known as Los Insurgentes.

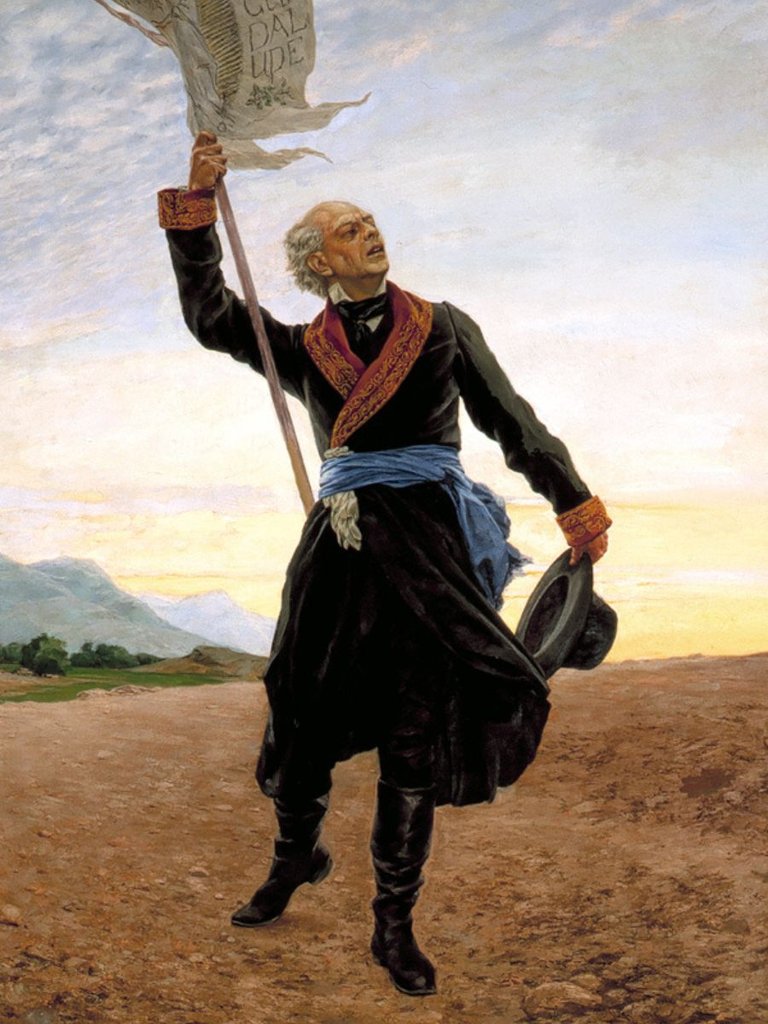

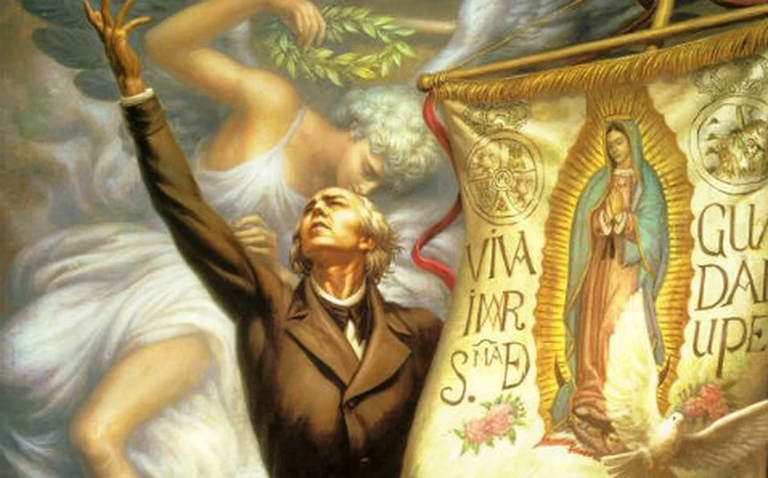

On September 16th 1810, as part of a mass he was celebrating, Miguel Hidalgo called out publicly for the rebellion against the viceroy in his famous Grito de Dolores. He knew the conspiracy was about to be discovered, and in this cry he finally brought the struggle out into the open. This moment is still celebrated each year as the declaration of Mexico's independence, where the incumbent president rings the same bell Hidalgo rang at the church of Dolores.

The result of the cry was an outstanding support from Mexicans from all walks of life. Even though the firmest pillars of society, namely the monarchy and the catholic church, were supposed to be preserved, each level of society had certain hopes for improvement of their situation, promised by possible independence. However, the way there turned out to be long and hard.

After the first successful battles Allende and Hidaglo ended up losing, getting captured, and ultimately being executed, with their heads displayed publicly to discourage further insurgencies. They remained there for over ten years, until Mexico finally gained its independence in 1821, and the insurgents were treated with the honor they are given today. Their physical remains were all brought to the capital, and today they are stored inside the Column of Independence, serving as their mausoleum.