Drill Baby Drill

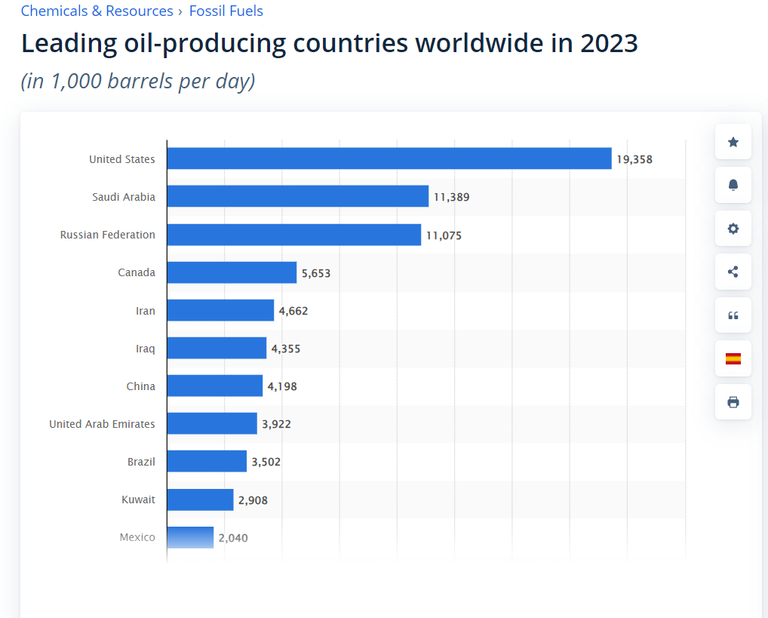

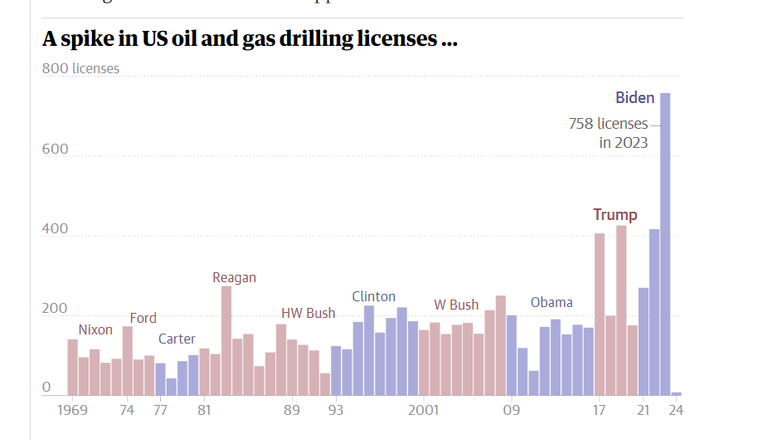

In recent years, America has ramped up its own oil production, moving closer to energy independence and reducing its reliance on OPEC, which, let's be honest, hasn't always been the most reliable partner. By doing so, the U.S. is steadily gaining market share in the global oil arena, with American oil giants—like my favorite, Exxon Mobil—emerging as some of the biggest winners. And with continued support from favorable policies, this trend is likely to keep rolling.

But how did the U.S. manage this, especially when everyone once thought American oil production had peaked back in 1970? The answer: fracking.

Fracking

Fracking, or hydraulic fracturing, is the process of pumping high-pressure fluid into underground rock formations to break them open and release trapped oil and gas. When combined with horizontal drilling, fracking became a revolutionary way to access oil and gas in tight rock formations that were once unprofitable or impossible to extract. But this breakthrough didn't come cheap—or without risks.

Enter Debt

To fund the expensive and relentless pace of shale drilling, companies turned to debt markets. Wall Street was all in, viewing shale as a high-growth sector with the promise of lucrative returns. From 2010 to 2020, U.S. shale companies took on an estimated $300 billion in debt, using the funds to acquire land, invest in drilling infrastructure, and boost production. All of this banked on high oil prices to make it pay off.

Who Will Pay the Bill?

Investors and Lenders

Much of this debt was financed through bonds and loans from investors and banks. When shale companies default or go bankrupt—as many did after the oil price crashes in 2014 and 2020—lenders and bondholders often face significant losses. Some investors, especially private equity firms, have already written off large amounts, realizing these debts may never be fully repaid.

Taxpayers

In some cases, the government has stepped in to support struggling energy companies through bailouts or tax breaks. During economic crises, for instance, some energy companies qualify for relief packages, indirectly passing part of the cost onto taxpayers.

Local Economies and Workers

When shale companies collapse or cut back, it hits local economies hard. In areas where shale oil was a major employer, layoffs and lost incomes impact communities, leading to a ripple effect that affects local businesses, public services, and overall economic stability.

So the only way all this debt can ever be repaid is if the prices are close to 100$ per barrel. And that is the reason that i believe the prices will never fall under 50$-60$ again unless a black swan event or an oil war breaks out.

Posted Using InLeo Alpha