Writing What I’ve Long Delayed: My First Words on Biblical Inerrancy

Among my series of lectures in Systematic Theology 1, biblical inerrancy is the topic that I have been planning to write about for so long, but have been prevented from due to many reasons. I hope that this time, in writing this article, I can write my first piece that will later be integrated into a 3-hour lecture session.

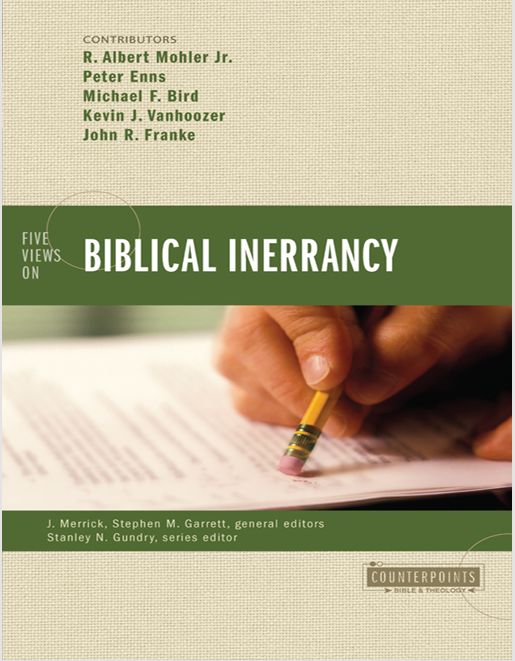

To achieve this goal, the book that I want to review and reflect on is Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy by Counterpoints. The contributors were “two systematic theologians (John Franke and Kevin Vanhoozer), two biblical scholars (Michael Bird and Peter Enns), and one historical theologian (Albert Mohler)" [p. 20]. In this article, I only intend to touch on the first 74 pages out of 361. These pages cover the introduction, Albert Mohler’s stance, and the two responses from Peter Enns and Kevin Vanhoozer. Due to the limitation of time, I intentionally skipped John Franke and Michael Bird. If I have the chance to continue this writing project, I plan to pick up the second chapter by Peter Enns and the fourth chapter by Kevin Vanhoozer, together with the corresponding responses from two authors (Mohler and Vanhoozer’s responses on Enns and Mohler and Enns’ responses on Vanhoozer).

The ideal end product of this writing project or lecture is to integrate the ideas of Mohler, Vanhoozer, and Franke, starting from the “classical” view to a renewal of “inerrancy by recovering Christian tradition” via linguistics and by addressing “concerns of colonialism and missiology” (ibid.).

Introduction

In introducing the book, J. Merrick and Stephen M. Garrett identified inerrancy as a hot evangelical issue. This time, the critics are not from outside but from within the evangelical circle. For those who hold to the “classic” view, they see inerrancy as essential to evangelical identity. The editors identified the Geisler-Gundry controversy to illustrate the sensitivity of this subject.

Robert Gundry resigned from ETS in 1983 as a result of Norman Geisler’s campaign. Geisler interpreted Gundry’s commentary on Matthew as a departure from the classical view of inerrancy. In Geisler’s mind, the idea that the midrash portion of the infancy narratives is not taken as factual reports is an attack against biblical inerrancy. As for Gundry, he “felt that Geisler was insensitive to premodern forms of communication” (p. 9).

Understanding Inerrancy in Relation to Basic Theological Commitments

One of the goals in publishing the book is to locate the discussion of biblical inerrancy in the context of prior biblical commitments. As such, it cannot be separated from our concept of God, revelation, and redemption.

Revelation

Properly speaking, the appropriate place of inerrancy in theological discussion is under revelation. The God who exists did not remain silent. He did not isolate Himself from His creation. He communicated knowledge to man—knowledge about Him and His creation, especially man.

For the editors, to emphasize “the factuality of Christianity” and thus make biblical inerrancy the head of Christian doctrine is to disconnect it from its context in biblical revelation, which would eventually result “in a diminishment of Christian truth,” which the authors understand as referring to existential reality rather than to just mere affirmation of facts (ibid.). Here’s how they explain the unhealthy outcome of such an emphasis:

Placing inerrancy at the outset of doctrinal statements seems to teach that Christian beliefs are of the order of facts. As we have suggested, facts can usually be assimilated into the self without much modification of the self, without a deep existential and moral reordering. Consequently, the Christian is taught that becoming a Christian is about learning the right information rather than submitting to the regeneration of the Holy Spirit (pp. 10-11).

Hence, a misplaced doctrine of inerrancy leads to overinflated perceptions of our knowledge of truth when this doctrine is not bracketed by larger considerations of general and special revelation as well as of the relationship between revelation and reason, all of which are typically treated in the doctrine of revelation (pp. 11-12).

To elaborate their understanding of Christian truth, the editors cited earlier the description of the New Testament regarding “events of our salvation as events of new creation” (p. 10).

The transformation effected in the events of Christian faith is rather different from a mere alteration of the general course of human history. What happens in Jesus Christ is nothing short of a reconstitution of the created order and the human being. Therefore, knowing the reality of Christ is not like knowing how the colonies won the Revolutionary War or the meaning of the Constitution of the United States. We can assimilate these truths into our repository of knowledge without much modification of ourselves or even our understanding of the world (ibid.).

Bibliology

Since the doctrine of revelation is divided into two categories, general and special, biblical inerrancy must be understood as a subset of special revelation. As such, the attributes of the Holy Scriptures, such as their necessity, authority, sufficiency, and clarity, must be taken into consideration. These attributes cannot be separated from the idea of biblical inspiration, which qualifies inerrancy.

These claims about Holy Scripture can be made only by first discussing the inspiration of Scripture, and thus, inspiration qualifies inerrancy. Of course, the doctrine of Holy Scripture itself is a subset of the doctrine of revelation, and the doctrine of revelation is a subsidiary of the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, Christology, and ultimately the triune God (p. 12).

Among the four attributes of the Bible, the editors picked up sufficiency and authority and wanted to clarify how we understand these terms.

Speaking of sufficiency, they asked:

Does it mean that what Scripture says is adequate for us to have true faith, but that such knowledge could be expanded by engagement with other sources so long as such expansion does not compromise the knowledge gained in Scripture? (ibid.).

Shifting to authority, they elaborate:

In modern scientific culture, the only ideas that have authority (or rationality) are those rooted in fact, and thus, if the factuality of Scripture is demonstrated, Scripture is made an authority. This is where some theologians would want to argue that inerrancy should be developed within a larger conception of divine authority (p. 13).

Then they raised a follow-up question:

If so, does this mean that Christians can defer to science on physical or historical matters and heed Scripture only when it touches on higher truths? Here, the scope of revelation and its relationship to natural knowledge are important for understanding the scope of inerrancy (p. 14).

Soteriology

Another branch of theology that must be considered to have a proper understanding of inerrancy is the doctrine of salvation. Since revelation is not an end in itself but serves a larger purpose, which is the salvation of God’s people, the discussion of inerrancy must not be detached from the doctrine of salvation. Here, the editors ask,

What constitutes saving knowledge of God? Is it a perfectly accurate understanding of historical events, physical laws, biology, and so on, or is it a moral and spiritual relationship with God? (ibid.).

And then they also touched on the progressive character of revelation and the history of salvation.

But this seems to admit that God does not exhaustively reveal himself or his salvation in any one moment, but revelation develops over time. . . We look at the Bible as completed, but it was not always so (ibid.).

Back to Inspiration

I find the discussion under inspiration something curious. I never expected that biblical scholars debate between authorial intent and the text. As for me, they are the same, though the sentence construction of the meaning might differ.

The editors returned to the Geisler-Gundry controversy to explain this matter. The topic under debate is the locus of meaning. For Gundry, the locus of meaning lies in the authorial intent, whereas Geisler finds it in the biblical text. Again, Geisler’s position implies that biblical “inerrancy implied verbal plenary inspiration,” which the editors understand as in:

. . . the text (what) we have is verbatim the text God inspired, down to the very terminology and syntax. It is not that God gave human authors a general impression or message that they then communicated in their own words and according to their understanding. Rather, God accommodated his message to each author’s style and understanding, even as such did not interfere with the content (p. 15).

However, those who argue to the contrary think that the above position “is destructive of human agency and reduces inspiration to dictation” (ibid.). What we need is a doctrine of inspiration that does not destroy human agency. If we follow Geisler’s position, does it mean that locating the locus of meaning in the text destroys human agency? If we follow Gundry, on the other hand, how does God secure an inerrant text without destroying human agency?

I think I must end here. I didn't expect that this article would take this long, and I am not done yet. I have to leave Albert Mohler's stance and the responses of Peter Enns and Kevin Vanhoozer to Mohler's position for the next article. At least, I am satisfied that I completed an initial article of this long-delayed lecture on inerrancy.

Grace and peace!

Posted Using INLEO

https://www.reddit.com/r/ChristiansPH/comments/1klpmsh/an_article_on_biblical_inerrancy_papaano/

This post has been shared on Reddit by @rzc24-nftbbg through the HivePosh initiative.

That's not an easy read, very philosophical and I probably would have issues even if it was in Italian lol

!PIZZA

You're right. If I can only complete the three chapters I mentioned, that would be a satisfying accomplishment for me.

!PIZZA

!LOLZ

lolztoken.com

It was just so lava-able.

Credit: belhaven14

@davideownzall, I sent you an $LOLZ on behalf of rzc24-nftbbg

(1/10)

Delegate Hive Tokens to Farm $LOLZ and earn 110% Rewards. Learn more.

Could you publish it somewhere like a sort of small book? Or just e-book version, I think it might be worth it

!PIZZA

Thank you for the suggestion. Once I am done, I will reconsider it.

!PIZZA

!LOLZ

lolztoken.com

He was resisting a rest.

Credit: reddit

@davideownzall, I sent you an $LOLZ on behalf of rzc24-nftbbg

(1/10)

$PIZZA slices delivered:

@rzc24-nftbbg(2/10) tipped @davideownzall (x2)

davideownzall tipped rzc24-nftbbg (x2)

Come get MOONed!

https://x.com/lee19389/status/1922430482710466864

#hive #posh

@angelann12 @bordagul @cooperpilgrim @matthewice @eonniechan23 @ivan51204 @moris1

Here is your reading assignment for this week.

@jmricalde @roylyn @arcelcalvin9 @grave2garden2025 @kopiko-blanca @arlenec2021 @donyabhuding12 @axietrashgame

You might find the book and this article interesting. Kindly check it.

!hivebits

rzc24-nftbbg, you mined 1.0 🟧 HBIT. If you'd replied to another Hive user, the HBIT would be split: 0.9 to you and 0.1 to them as a tip. When you mine HBIT, you're also playing the Wusang: Isle of Blaq game. 🏴☠️

Sorry, but you didn't find a bonus treasure token today. Try again tomorrow...they're out there! Your random number was 0.6609731140426751, also viewable in the Discord server, #hbit-wusang-log channel. | tools | wallet | discord | community | daily <>< Check for bonus treasure tokens by entering your username at a block explorer A, explorer B, or take a look at your wallet.There is a treasure chest of bitcoin sats hidden in Wusang: Isle of Blaq. Happy treasure hunting! 😃 Read about Hivebits (HBIT) or read the story of Wusang: Isle of Blaq.