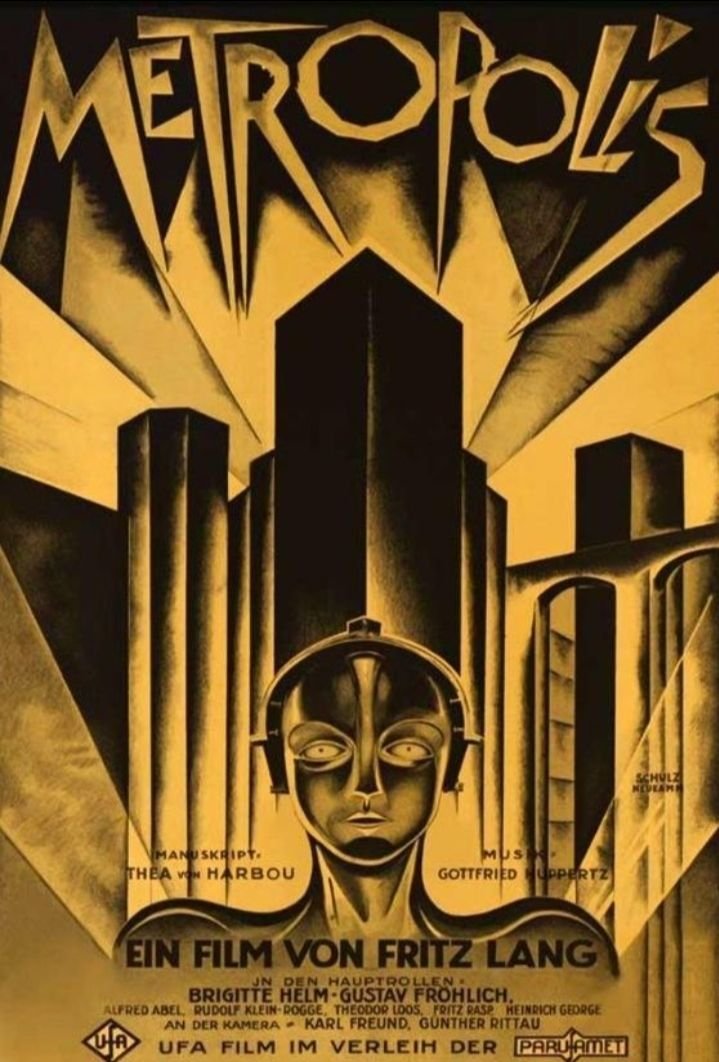

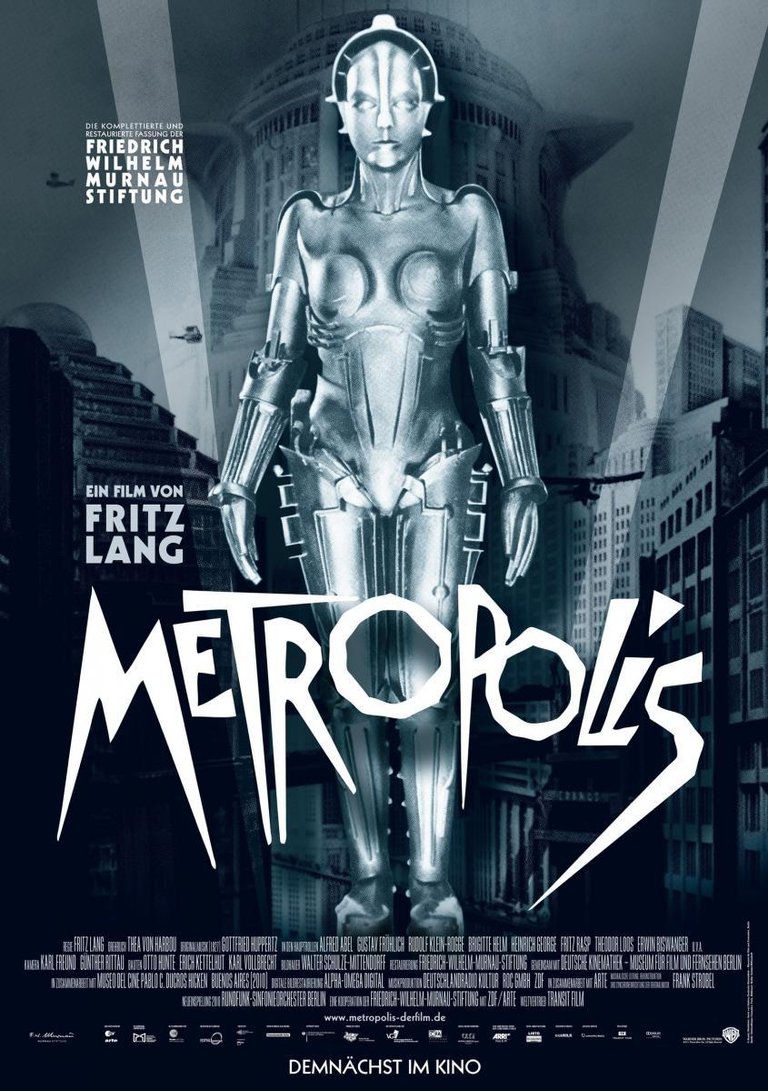

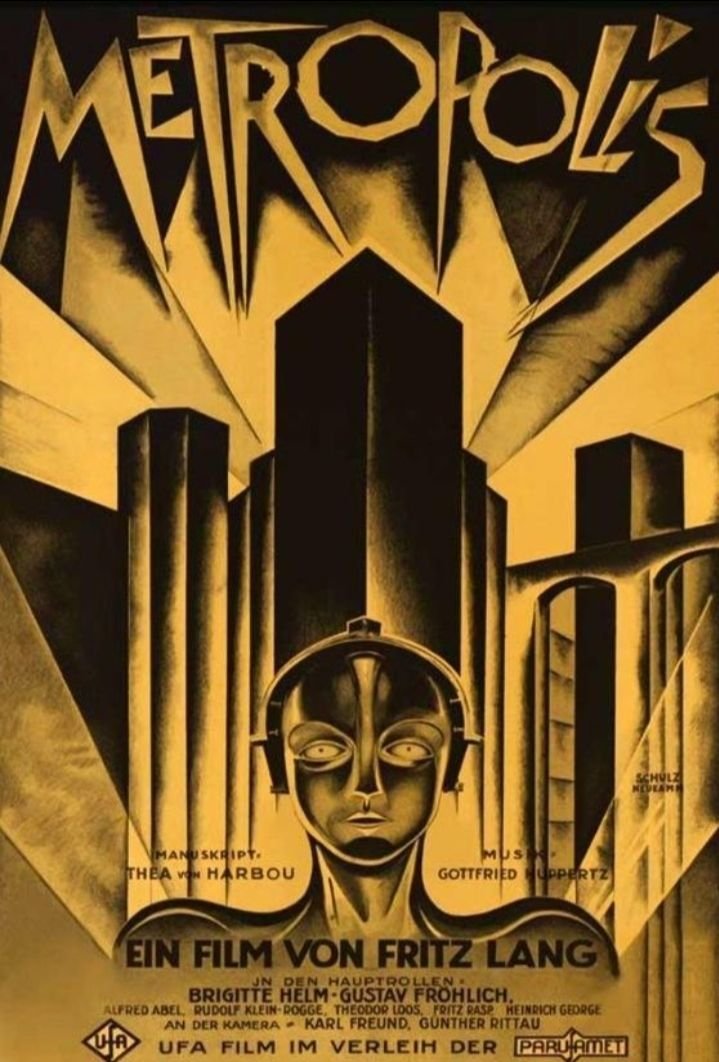

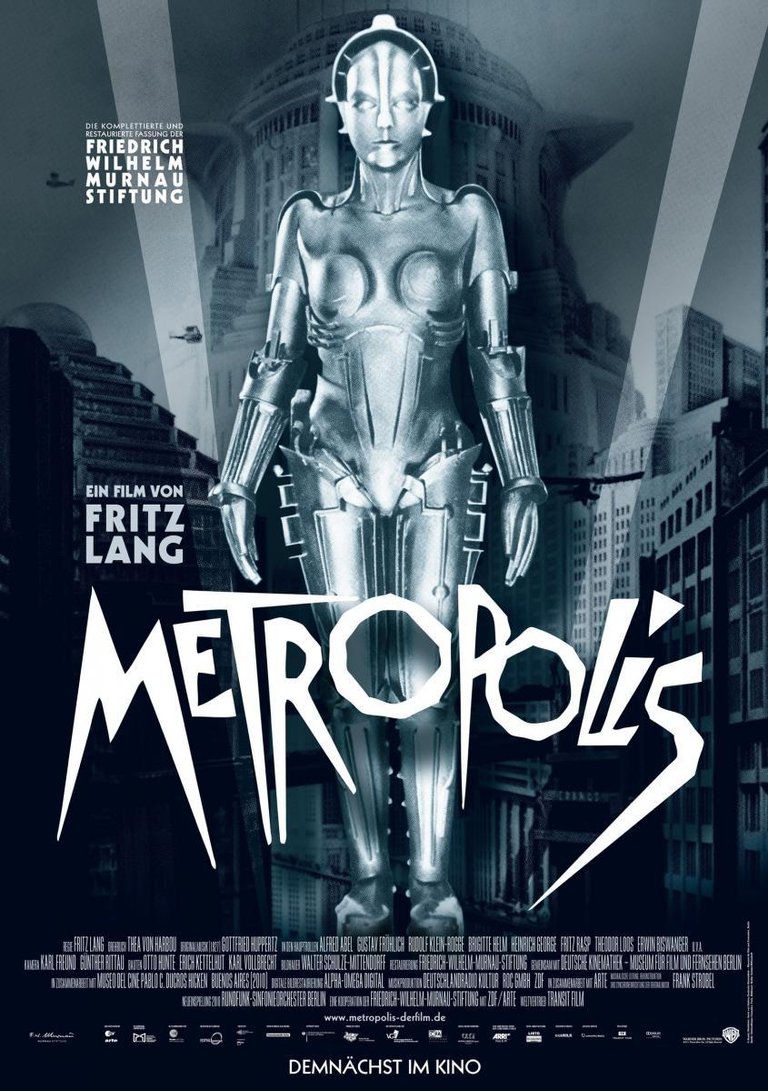

Ten Films That Shook the World "Metropolis"|Diez películas que estremecieron al mundo "Metrópolis"( ENG-ESP)

Source: FilmAffinity

When the Nazis offered Fritz Lang the chance to direct propaganda films, he fled to the US that same night. His wife, Thea von Harbou, stayed... and joined the Nazi Party.

Metropolis, Fritz Lang's work, is a film that, almost a century after its release, continues to shock.

What makes it great?

Its dystopian vision, its social critique, and its masterful staging. That's why it's my second proposal for the series "Ten Films That Shook the World."

It's a classic not only for its influence, but also for its reflection on class struggle. When we see it for the first time, we think it's a museum piece or perhaps a gem of silent cinema. But it's much more than that, dear hivers of #cinetv.

This film has a prodigious ability to connect with today's viewers.

Fritz Lang (Vienna, 1890 – California, 1976) constructs a fascinating universe with this film. The monumental architecture, the choreography of the working masses, and the iconic figure of Maria, the automaton, are unforgettable images.

The production design, by Erich Kettelhut, Karl Vollbrecht, and Otto Hunte, is a true marvel of imagination. It masterfully combines industrial and art deco aesthetics, achieving a vision of modernity that is as fascinating as it is disturbing. Each frame becomes a work of art: impeccable geometric compositions that reinforce the atmosphere of dehumanized control and alienation.

However, where Lang's film truly reaches its full potential is in its capacity to shock. The shift change sequence, with the workers marching like automatons, or the vision of "Moloch," the machine that devours the workers, are moments of unsurpassed visual and emotional intensity. The horror of work, the dehumanization of the human being reduced to a cog, is a recurring theme in the film, and Lang addresses it with a rawness that rivals even more modern works.

Source: FilmAffinity

The opening shot of Metropolis says it all: a succession of gigantic gears moving in unison, pistons rising and falling like hearts of steel, workers marching in perfect rows toward the factories. They are not men, they are extensions of the machine. Fritz Lang filmed this in 1927, but it could just as easily have been made today. Therein lies its greatness: Metropolis didn't predict the future, it diagnosed it. Every image, every sequence, is our own reality, and it hurts because we still haven't learned the lesson.

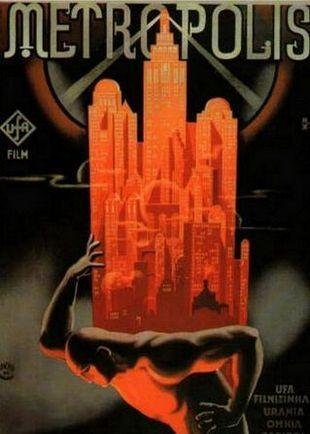

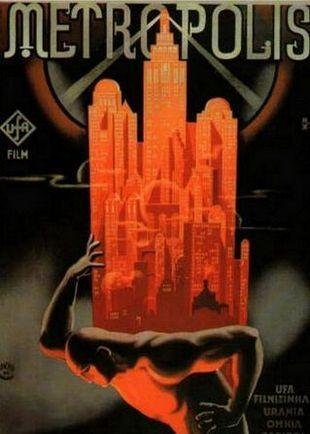

The film divides the world in two: above, the city of the masters, with its hanging gardens and towers that pierce the clouds. Below, the catacombs where the workers live, ghosts that keep the rich's utopia running.

Young Freder, son of the master of Metropolis, discovers this hell when he follows Maria, a woman who preaches peace to the oppressed. What he sees marks him forever: men turned into numbers, machines that devour lives, children growing up in the rusty pipes. The scene where a worker collapses from exhaustion and is sucked into the gears remains one of the most brutal ever filmed. There's no blood, but the horror is palpable.

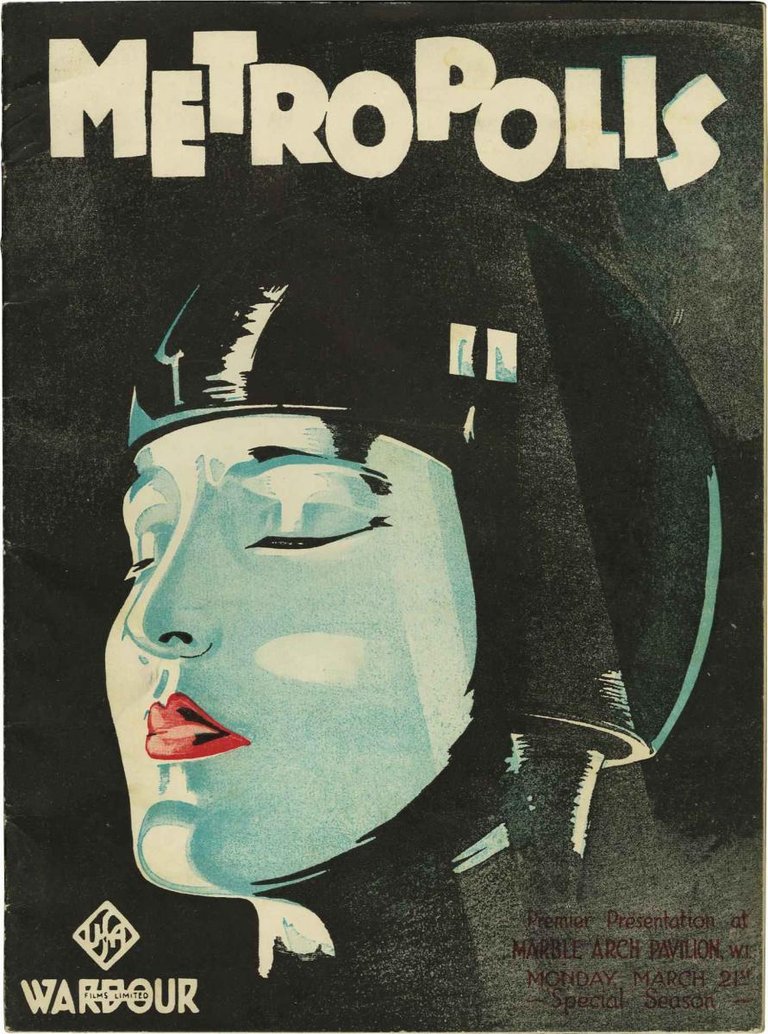

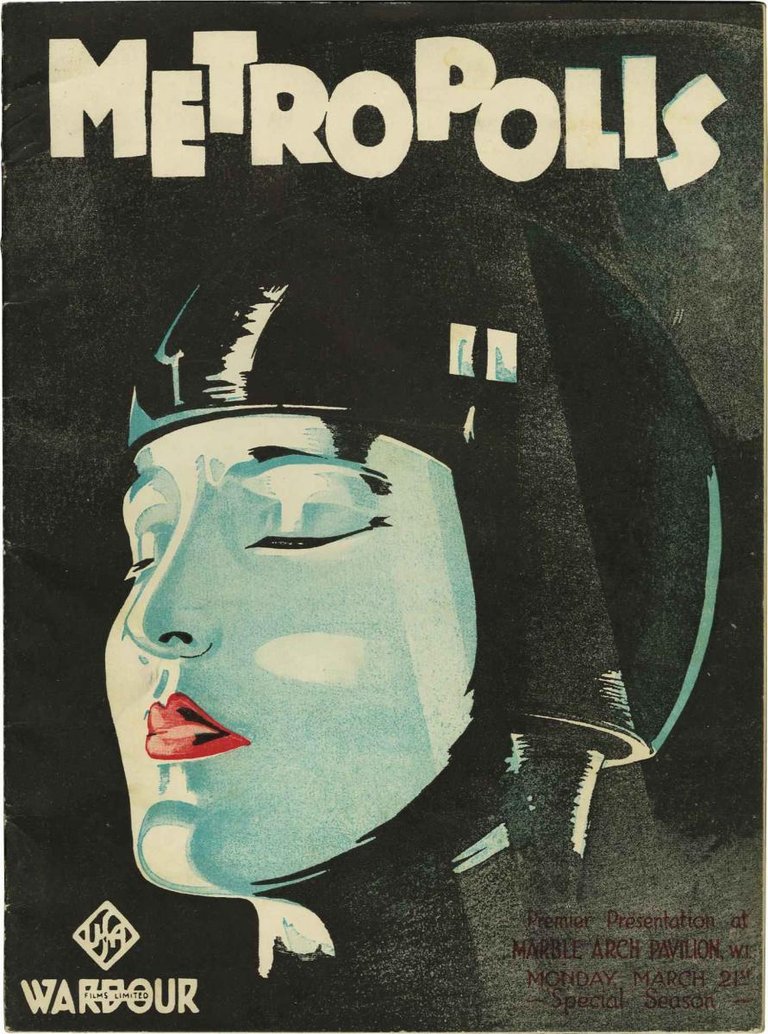

Source: FilmAffinity

Maria is the soul of the film. In the catacombs, surrounded by starving children, she tells the story of the Tower of Babel: how those who built it ended up not understanding each other. Her message is one of hope, but power does not tolerate dissenting voices. Joh Fredersen, Freder's father, orders the creation of a robotic copy of Maria to manipulate the masses. What follows is pure nightmare: the robot Maria dances half-naked before the rich, inciting sin, while sowing hatred in the poor neighborhoods. The scene where the robot comes to life, surrounded by electricity, its metallic body shining beneath a fake skin, is one of the most iconic moments in cinema.

Chaos erupts when the workers, tricked by the robot, destroy the machines that enslave them. But their rebellion brings them to the brink of infanticide: unwittingly, they flood the slums where their children are.

Lang films this like a biblical tragedy: the water rises, the children cry, the mothers scream. Freder and the real Maria fight against the human tide, but the damage is already done. It is here that the film reaches its emotional climax: not in the action, but in the despair of those who realize they have been manipulated into self-destruction.

The ending, with its message of reconciliation between hands and brains mediated by the heart, seems like an easy consolation. But Lang's genius lies in the ambiguity: has anything really changed? The workers return to their machines, the rich remain in their towers, and Freder becomes a symbolic bridge. The power structure remains intact. This is why Metropolis remains relevant: it offers no solutions, it only shows the abyss.

Technically, the film was a miracle. The robot special effects, the monumental sets, the use of shadow and light—everything was groundbreaking. Lang built an entire city in the studio, with miniature skyscrapers and thousands of extras. The result is a work that feels alive and organic, despite its mechanical subject matter. The Tower of Babel sequence, animated with pioneering techniques, remains dazzling.

Source: FilmAffinity

More than a film, Metropolis is a modern myth. It speaks to the alienation of labor, the gap between rich and poor, and how technology can oppress rather than liberate. Its images have influenced everything from Blade Runner to Black Mirror. But its true power lies in how it confronts us with uncomfortable questions: Are we freer than those workers? Or have we simply traded steel chains for algorithms?

Ninety-seven years later, Metropolis continues to shock us because, deep down, we all live in it.

The German film production company UFA spent 5 million marks on this film, equivalent to about $200 million today, and nearly went bankrupt. Lang filmed for 16 months, using 37,000 extras, including children with shaved heads to simulate worker baldness.

It was worth it.

MY RATING

- Technical Innovation: ★★★★★ (Invented cyberpunk decades before the term).

- Narrative: ★★★☆☆ (Symbolic but schematic; the missing original editing hinders its fluidity).

- Performances: ★★★★☆ (Helm is electrifying; Fröhlich is excessive but moving).

- Legacy: ★★★★★ (It influenced everything from Star Wars to Blade Runner 2049).

FINAL SCORE: 9.5/10 – A cathedral of cinema that still looks back at us from the future.

🎞️. Original Content

🎞️ Images referenced and created with Gemini AI

🎞️ Translation using Google Translation

Diez películas que estremecieron al mundo "Metrópolis"

Fuente: FilmAffinity

Cuando los nazis le ofrecieron a Fritz Lang dirigir cine propagandístico, huyó a EE.UU. esa misma noche. Su esposa, Thea von Harbou, se quedó... y se unió al partido nazi.

Metrópolis, la obra de Fritz Lang, es una película que, a casi un siglo de su estreno, sigue conmocionando.

¿Qué la hace grande?

Su visión distópica, su crítica social y su magistral puesta en escena. Por eso es mi segunda propuesta para el ciclo "Diez películas que estremecieron al mundo".

Es un clásico no solo por su influencia, sino por reflexión sobre la lucha de clases. Cuando la vemos por primera vez pensamos que es una pieza de museo o quizás una joya del cine silente. Pero es mucho más que eso querido hivers de #cinetv

Esta película tiene una capacidad prodigiosa para conectar con el espectador de hoy.

Fritz Lang (Viena, 1890-California 1976), con con esta cinta construye un universo fascinante. La arquitectura monumental, la coreografía de las masas obreras, la figura icónica de Maria, la autómata, son imágenes grabadas inolvidables.

El diseño de producción, obra de Erich Kettelhut, Karl Vollbrecht y Otto Hunte, es un auténtico prodigio de imaginación. Combina con maestría la estética industrial y el art déco, logrando una visión de la modernidad tan fascinante como inquietante. Cada fotograma se convierte en una obra de arte: composiciones geométricas impecables que refuerzan la atmósfera de control deshumanizado y alienación.

Sin embargo, donde la película de Lang adquiere su verdadera dimensión es en su capacidad para estremecer. La secuencia del cambio de turno, con los obreros desfilando como autómatas, o la visión del "Moloch", la máquina que devora a los trabajadores, son momentos de una intensidad visual y emocional insuperables. El horror del trabajo, la deshumanización del ser humano reducido a un engranaje, es un tema recurrente en la película, y Lang lo aborda con una crudeza que no tiene nada que envidiar a las obras más modernas.

Fuente: FilmAffinity

El primer plano de Metrópolis lo dice todo: una sucesión de engranajes gigantescos moviéndose al unísono, pistones que suben y bajan como corazones de acero, obreros marchando en filas perfectas hacia las fábricas. No son hombres, son extensiones de la máquina. Fritz Lang filmó esto en 1927, pero bien podría ser hoy. Ahí radica su grandeza: Metrópolis no predijo el futuro, lo diagnosticó. Cada imagen, cada secuencia, es nuestra propia realidad, y duele porque seguimos sin aprender la lección.

La película divide el mundo en dos: arriba, la ciudad de los amos, con sus jardines colgantes y torres que rasgan las nubes. Abajo, las catacumbas donde viven los obreros, fantasmas que mantienen en funcionamiento la utopía de los ricos.

El joven Freder, hijo del amo de Metrópolis, descubre este infierno cuando sigue a María, una mujer que predica paz entre los oprimidos. Lo que ve lo marca para siempre: hombres convertidos en números, máquinas que devoran vidas, niños que crecen en las tuberías oxidadas. La escena donde un obrero colapsa agotado y es absorbido por los engranajes sigue siendo una de las más brutales jamás filmadas. No hay sangre, pero el horror es palpable.

Fuente: FilmAffinity

María es el alma de la película. En las catacumbas, rodeada de niños hambrientos, cuenta la historia de la Torre de Babel: cómo los mismos que la construyeron terminaron sin entenderse. Su mensaje es de esperanza, pero el poder no tolera voces disidentes. Joh Fredersen, el padre de Freder, ordena crear una copia robótica de María para manipular a las masas. Lo que sigue es pura pesadilla: el robot-María baila semidesnuda ante los ricos, incitando al pecado, mientras en los barrios pobres siembra el odio. La escena donde el robot cobra vida, rodeada de electricidad, con su cuerpo metálico brillando bajo una piel falsa, es uno de los momentos más icónicos del cine.

El caos estalla cuando los obreros, engañados por el robot, destruyen las máquinas que los esclavizan. Pero su rebelión los lleva al borde del infanticidio: sin darse cuenta, inundan los barrios bajos donde están sus hijos.

Lang filma esto como una tragedia bíblica: el agua sube, los niños lloran, las madres gritan. Freder y la verdadera María luchan contra la marea humana, pero el daño ya está hecho. Es aquí donde la película alcanza su clímax emocional: no en la acción, sino en la desesperación de quienes se dan cuenta de que han sido manipulados para destruirse a sí mismos.

El final, con su mensaje de reconciliación entre manos y cerebro mediados por el corazón, parece un consuelo fácil. Pero la genialidad de Lang está en la ambigüedad: ¿realmente cambió algo? Los obreros regresan a sus máquinas, los ricos siguen en sus torres, y Freder se convierte en un puente simbólico. La estructura de poder permanece intacta. Esta es la razón por la que Metrópolis sigue vigente: no ofrece soluciones, solo muestra el abismo.

Técnicamente, la película fue un milagro. Los efectos especiales del robot, los escenarios monumentales, el uso de la sombra y la luz: todo fue innovador. Lang construyó una ciudad completa en estudio, con rascacielos en miniatura y miles de extras. El resultado es una obra que se siente viva, orgánica, a pesar de su temática mecánica. La secuencia de la torre de Babel, animada con técnicas pioneras, sigue siendo deslumbrante.

Fuente: FilmAffinity

Más que una película, Metrópolis es un mito moderno. Habla de la alienación laboral, de la brecha entre ricos y pobres, de cómo la tecnología puede oprimir en lugar de liberar. Sus imágenes han influenciado todo, desde Blade Runner hasta Black Mirror. Pero su verdadero poder está en cómo nos confronta con preguntas incómodas: ¿Somos más libres que esos obreros? ¿O solo hemos cambiado las cadenas de acero por algoritmos?

Noventa y siete años después, Metrópolis sigue estremeciendo porque, en el fondo, todos vivimos en ella.

La UFA productora de cine alemana gastó en esta película 5 millones de marcos, equivalente a unos $200 millones actuales, y casi se arruinó. Lang filmó durante 16 meses, usando 37,000 extras, incluidos niños con cabezas rapadas para simular calvicie obrera.

Valió la pena.

MI CLASIFICACIÓN

- Innovación técnica: ★★★★★ (Inventó el cyberpunk décadas antes del término).

- Narrativa: ★★★☆☆ (Simbólica pero esquemática; el montaje original perdido lastra su fluidez).

- Actuaciones: ★★★★☆ (Helm es electrizante; Fröhlich, excesivo pero conmovedor).

- Legado: ★★★★★ (Influenció desde Star Wars hasta Blade Runner 2049).

PUNTUACIÓN FINAL: 9.5/10 – Una catedral del cine que aún hoy nos mira desde el futuro.

🎞️. Contenido Original

🎞️ Imágenes referenciadas y creadas en Gemini AI

🎞️ Traducción en Google Translation

Metrópolis es realmente una película espectacular. El tema de los seres humanos consumidos en su labor enajenados del resto del mundo como bien dices. Como extensión de las máquinas es un tema recurrente en la literatura también. Además la historia de los dueños del mundo encima de los oprimidos y que otros dirían el bajo mundo se refleja en muchas películas principalmente de CiFi lo que demuestra la impotencia de metrópolis como punto de partida.

Absolutamente.

Tiene muchísima razón en lo que dices. Me alegro que la gente joven se acerque a estos clásicos para entender de dónde viene la cosa.

Gracias por llegarte!

No la he visto completa, solo escenas sueltas, y es impresionante, realmente impresionante.

Gracias por la recomendación 🤗

Todo en la vida merece una segunda y hasta una tercera oportunidad.

Verás cómo la disfrutas!!🌿

Recuerdo muy bien cuando ví la película hace unos cuantos años, me encantó la creatividad que muestra y sobre todo lo avanzado de las ideas para la época. Luego me entristeció mucho saber que de la película se conserva solo una parte del metraje original, es triste descubrir que hasta una obra maestra como esa perdió una parte, quizás debido a la inacción o al desconocimiento.

Según leí mientras me preparaba para elaborar esta publicación en Buenos Aires apareció una copia completa.

Un abrazo! 🌿

Confieso que no la he visto. Prometo buscarla ahora 🥰

Te hará bien.

Acercarte al arte genuino siempre es una buena opción.

Éxitos y buen provecho.

✨🌿

@tipu curate

Upvoted 👌 (Mana: 0/60) Liquid rewards.

Mi límite es los 80s y 70s, pero eso no significa que reconozca las grandes obras de antes de esto y que originaron e inspiraron lo que es el cine actual. Como fan de los especiales, admiro este tipo de reseñas que haces.

Muy buen post.