THE BABEL BUS OR REASONS FOR A TRIP/LA GUAGUA DE BABEL O MOTIVOS PARA UN VIAJE/(Eng.-Esp.)

Hello, dear friends of this community. Here I'm sharing a review I wrote of the book La guagua de Babel, winner of the Nicolás Guillén Prize in 2023, by the important Cuban writer Carlos Esquivel Guerra. I hope you like it, and that we can begin this wonderful journey into poetry together.

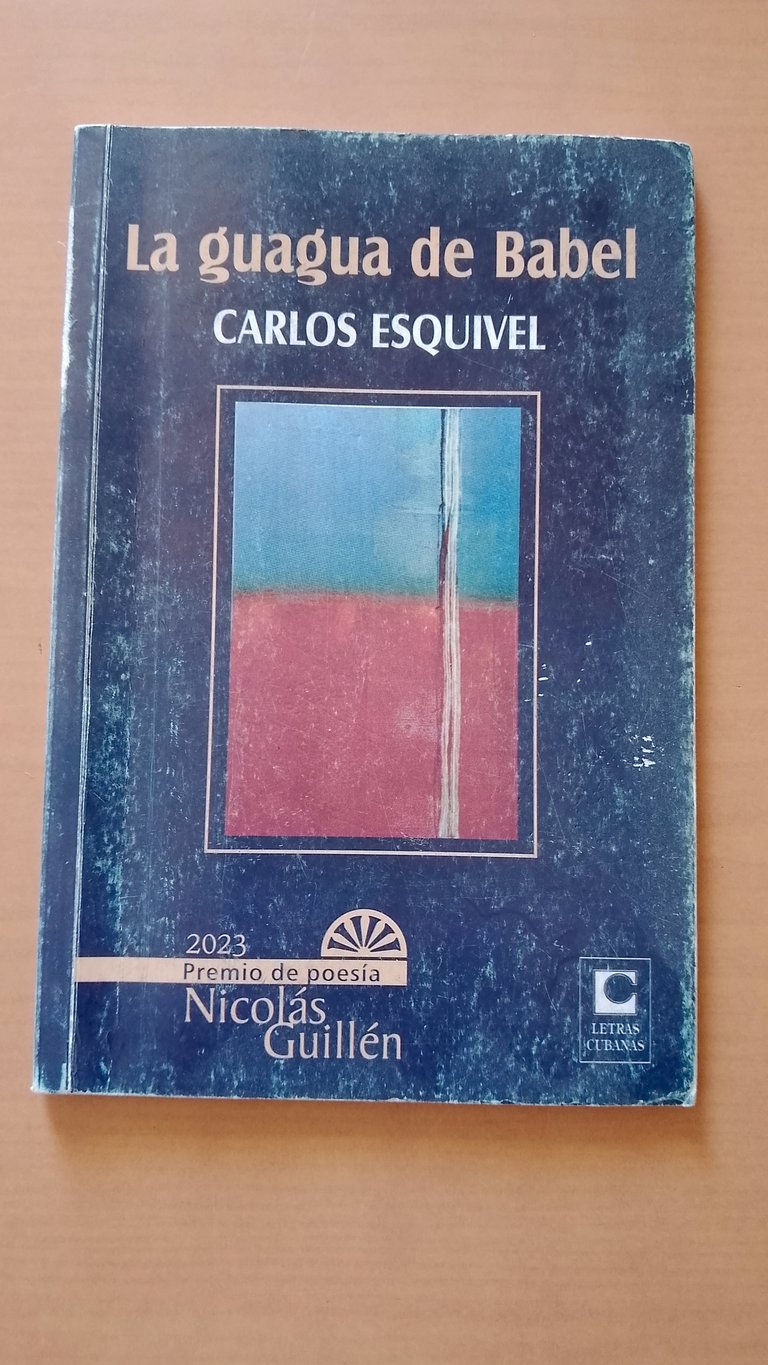

"This is the novel of no things, of no journeys," the opening fragment of the book La guagua de Babel, winner of the Nicolás Guillén Poetry Prize in 2023, by the writer from Las Tunas, Carlos Esquivel Guerra, published that same year by Letras Cubanas Publishing House.

From the very beginning of the work, the reader will notice certain inconsistencies between the genre of the work and the original statement of poem I. To this, as a kind of coincidental sarcasm, we can add what the Roman historian Flavius Josephus stated, similarly to what appears in Genesis 11:9, when he mentions that the word Babel has a Hebrew origin, meaning confusion.

Will Carlos manage to sell this book of poetry, which is presented to us a priori as a novel? Will Carlos be able to get a bus moving with just the announcement of the journey? What would be this bus's destination? Who are its passengers?

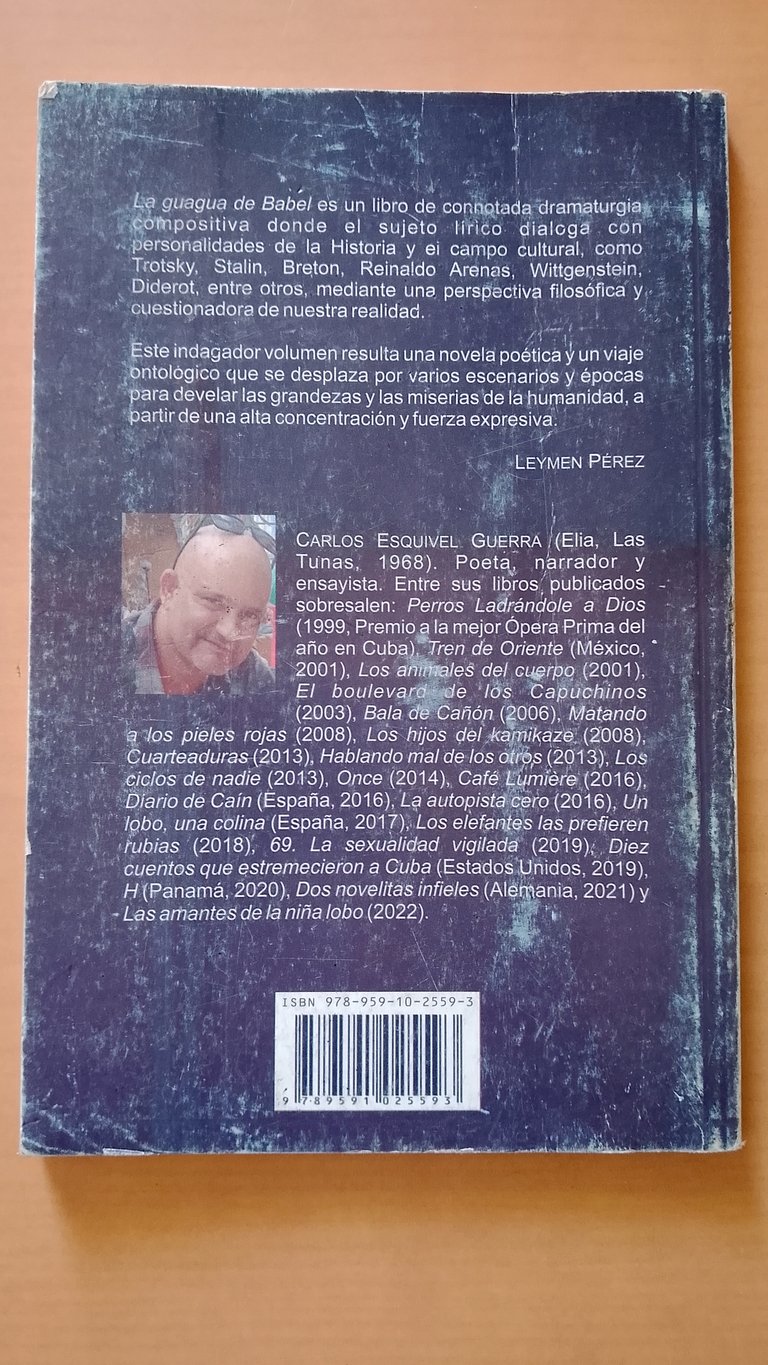

These and other questions (equally connotative) will mark the common thread in the analysis of a work where a prodigious maturity and a plausible evolution can be seen.Here, less can be more. In this book, Carlos sheds any vestments to reach and transgress with greater force the obligatory shortcuts. We had already recognized these skills (which are only acquired through experience and the search for new substrates) in poetry books such as: Zona negra (Black Zone), Editorial Sanlope, 2004; Los hijos del Kamikaze (Children of the Kamikaze), Editorial Letras Cubanas, 2008; and Cuarteaduras (Cuarteaduras), Editorial Oriente, 2013.

La guagua de Babel (The Baby of Babel) is composed of eighty-five texts, harmoniously organized based on the content of each text, into two sections, separated by a millimetrically blank page bearing, as a necessary tattoo, the following phrase by Jack Keroau: "...they must find me where they find the bandages of my shroud flying." I say precisely because the chronological order of each prose poem, based on Roman numerals, is uninterrupted; it maintains full speed like a bus that has set off on a sure path. Is that so? From my point of view, it was a good idea to dedicate the first part to the lyrical subject's interaction with great figures in history and culture, such as Trotsky, Stalin, Breton, Lenin, Reinaldo Arenas, Calvert Casey, Lourdes Casal, Gastón Baquero, Mireya Robles, among others.

In this chapter, if it could be called that, Carlos Esquivel moves, learns from each landscape he contemplates, engages in conversations, and is capable of creating analogies; he shines from his pain, he debates thoughtfully.

At times, he seems happy, but what is happiness if not internal harmony that manifests itself as a feeling of well-being that lasts over time, not as a temporary state of mind.

Just as his book overlaps with poem LIV, so does his happiness. Carlos travels, plays, celebrates, immerses himself in other cultures, visits cities: Tampa, Houston, Mexico, Madrid, Pennsylvania, but he always returns (at least that's what he's led us to believe) to the old, destroyed, perhaps invisible house. I travel because I can't wake up far from myself (Poem II, p. 10).

Throughout this chapter, there are words that reveal the poet's inner world that everyone wants to penetrate: mistakes, infidelity, travel. They are repeated again and again, like an emanation, like an interspersed echo.

In the second part of the book, we can find texts that make us understand in a very singular way, that whoever once left, is already at home, talking with his family and friends, but always dissatisfied, maladjusted: I went to seas to fish for whatever appeared from the non-seas: a sinking apostle, the flesh in an empty hole, the silences of my mother, the order of things if they suppose defeated matter, a country taking on water, the guardian who pretends to watch over places destined for me.

I returned from the seas as one returns from an ancient battle: the inner seam, the explainable pain in a new wrapping, the fishing rod upside down. (Poem LXV, p. 75)

Perhaps the bus used by Carlos, through poetry, to reach heaven (understanding this last as personal fulfillment) is the bus we all would like, or should reach, or not. Literature sometimes serves to show the real maps, the perfect palmistry. There is a subjective world behind the word, which must be discovered and interpreted.

In The Metaphysical Poets, T.S. Eliot distinguishes intellectual poets from reflective poets by their ability to integrate thought with emotion.

Intellectual poets like Tennyson and Browning excel at rational thought, but lack a deeper emotional commitment to their ideas, unlike reflective poets like Dante, who experience thoughts as profound emotional experiences.

Intellectual poets like Tennyson and Browning excel at rational thought, but lack a deeper emotional engagement with their ideas, unlike reflective poets like Dante, who experience thoughts as profound emotional experiences. Eliot suggests that while intellectual poets refine their language, their emotional depth is often shallow compared to reflective poets, who achieve a more mature balance of mind and emotion, potentially leading to more timeless poetry.

In line with the above, it can be said that, at least in this book, The Bus to Babel, Carlos presents himself as a reflective poet, which is appreciated because it makes us think, while forcing us to meditate, to discover, or try to discover, the exact place of peace, which is not the same as freedom, although different associations have been established.

It will suffice to announce the journey, because there is always a reason to travel. Behind the wall, someone is waiting for us with their heart in their hand. Someone requests our presence.

Hola, queridos amigos de esta comunidad. Aquí les comparto una reseña que hice al libro La guagua de Babel, premio Nicolás Guillén, 2023, del importante escritor cubano Carlos Esquivel Guerra. Espero les guste, e iniciemos juntos este maravilloso viaje a la poesía.

"Esta es la novela de las ningunas cosas, de los ningunos viajes", fragmento inicial del libro La guagua de Babel, Premio de Poesía Nicolás Guillén, 2023, del escritor tunero, Carlos Esquivel Guerra, publicado ese mismo año por la Editorial Letras Cubanas.

Desde el propio inicio de la obra, el lector podrá notar ciertas incongruencias entre el género de ésta, y el enunciado primigenio del poema I. A esto, como una especie de coincidente sarcasmo, podemos agregar lo expuesto por el historiador romano Flavio Josefo, de manera similar, a lo que aparece en Génesis 11:9, al referirse que el vocablo Babel tiene un origen hebreo, que significa confusión.

¿Logrará Carlos vender este libro de poesía que se nos presenta a priori como una novela? ¿Podrá Carlos echar a andar una guagua solo con la anunciación del viaje? ¿Cuál sería el destino de esta guagua? ¿Quiénes sus pasajeros?

Éstas y otras interrogantes (igual de connotativas) marcarán el hilo conductor en el análisis de una obra donde se aprecia una madurez portentosa, una evolución plausible.

Aquí menos puede ser más. Carlos se despoja en este libro de cualquier indumentaria para llegar y transgredir con mayor fuerza, los obligados atajos. Ya habíamos advertido estas habilidades (que solo se ganan con la experiencia, y la búsqueda en nuevos sustratos) en libros de poesía como: Zona negra, Editorial Sanlope, 2004; Los hijos del Kamikaze, Editorial Letras Cubanas, 2008; y Cuarteaduras, Editorial Oriente, 2013.

La guagua de Babel se compone de ochenta y cinco textos, organizados armónicamente, a partir del contenido de cada cual, en dos secciones, separadas milimétricamente por una hoja una hoja en blanco que lleva como tatuaje necesario, la siguiente frase de Jack Keroauc: “…tienen que encontrarme donde encuentran las vendas de mi mortaja volando”. Digo milimétricamente porque el orden cronológico de cada poema en prosa, a partir de números romanos, no se corta, se mantiene a toda velocidad como guagua que ha emprendido un camino certero. ¿Será?

Acertada, desde mi punto de vista, fue la idea de dedicar una primera parte a que el sujeto lírico confluyera con grandes personalidades de la Historia y la Cultura, como: Trotsky, Stalin, Breton, Lenin, Reinaldo Arenas, Calvert Casey, Lourdes Casal, Gastón Baquero, Mireya Robles, entre otros.

En este capítulo, si así pudiera llamarse, Carlos Esquivel se desplaza, aprende de cada paisaje contemplado, entabla conversaciones y es capaz de crear analogías; brilla desde el dolor, debate concienzudamente.

Por momentos pareciera feliz, pero qué es la felicidad, sino la armonía interna que se manifiesta como un sentimiento de bienestar que perdura en el tiempo y no como un estado de ánimo de origen pasajero.

Como mismo se superpone su libro en el poema LIV, así se superpone su felicidad. Carlos viaja, toca, celebra, se inmiscuye en otras culturas, visita ciudades: Tampa, Houston, México, Madrid, Pensilvania, pero siempre regresa (al menos eso nos ha hecho creer) a la casa vieja, destruida, quizás invisible. Viajo porque no puedo despertar lejos de mí (Poema II, pág. 10).

Hay palabras que develan, a lo largo de este capítulo, ese mundo interior del poeta al que todos quieren penetrar: errores, infidelidad, viajes. Una y otra vez se repiten, como una emanación, como un eco intercalado.

En la segunda parte del libro, podemos encontrar textos que nos dan a entender de una forma muy singular, que quien alguna vez partió, ya está en casa, conversando con su familia y amigos, pero siempre inconforme, inadaptado: Me fui a mares a pescar lo que apareciera de los no mares: un hundimiento de apóstol, la carne en agujero vacío, los silencios de mi madre, el orden de las cosas si suponen materia vencida, un país haciendo aguas, el guardián que finge cuidar sitios a mí destinados. Regresé de mares como se regresa de una batalla antigua: la costura interior, el dolor explicable en envoltura nueva, la caña de pescar cabeza abajo. (Poema LXV, pág. 75)

A lo mejor la guagua utilizada por Carlos, desde la poesía, para alcanzar el cielo (entiéndase esto último como realización personal) es la guagua a lo que todos quisiéramos, o debiéramos arribar, o no. La literatura en ocasiones sirve para mostrar los reales mapas, la quiromancia perfecta. Existe un mundo subjetivo detrás de la palabra, que debe ser descubierto e interpretado.

En Los poetas metafísicos, TS Eliot, distingue a los poetas intelectuales de los poetas reflexivos por su capacidad de integrar el pensamiento con la emoción.

Los poetas intelectuales como Tennysony Browning sobresalen en el pensamiento racional, pero carecen de un compromiso emocional más profundo con sus ideas, a diferencia de los poetas reflexivos como Dante, que experimentan los pensamientos como experiencias emocionales profundas. Eliot sugiere que, si bien los poetas intelectuales refinan el lenguaje, su profundidad emocional es a menudo superficial en comparación con los poetas reflexivos, que logran un equilibrio más maduro de mente y emoción, lo que potencialmente conduce a una poesía más atemporal.

En consonancia con lo anteriormente expuesto, se puede afirmar que, al menos en este libro, La guagua de Babel, Carlos se nos presenta como un poeta reflexivo, lo cual se agradece, porque nos hace pensar, a la vez que nos obliga a meditar, para descubrir o intentar descubrir, el sitio exacto de la paz, que no es lo mismo que la libertad, aunque se hayan establecido disímiles asociaciones.

Solo bastará con anunciar el viaje, porque siempre hay un motivo para viajar. Detrás del muro alguien nos espera con el corazón en la mano. Alguien reclama nuestra presencia.

Texto de mi propiedad, e imágenes tomadas al libro.