Did First-Century Jewish Rabbis Believe the Messiah Was Divine and Died for the World’s Sins?

Image Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zohar

By @linda2021 | Published July 16, 2025

As Messianic Jews, we believe Yeshua is the Mashiach, the divine Logos who created all things and became flesh, as declared in the Brit HaChadashah (John 1:1-14). But does this belief have roots in ancient Jewish thought? The Zohar, a mystical Jewish text, and other Second Temple sources suggest a divine Messiah tied to God’s creative Word (Vayomer) in Genesis, aligning with Yeshua’s identity. Modern Orthodox Judaism, shaped by Rashi and Ramban, rejects this, emphasizing a human Messiah. I believe this shift reflects a reaction to Christianity rather than the vibrant, diverse theology of ancient Judaism, including Pharisaic and Essene traditions. Let’s dive into the Zohar’s teachings, uncover ancient sources, and hear from Messianic Jewish scholars who connect these texts to Yeshua, revealing how modern Jewish theology diverged from its ancient roots.

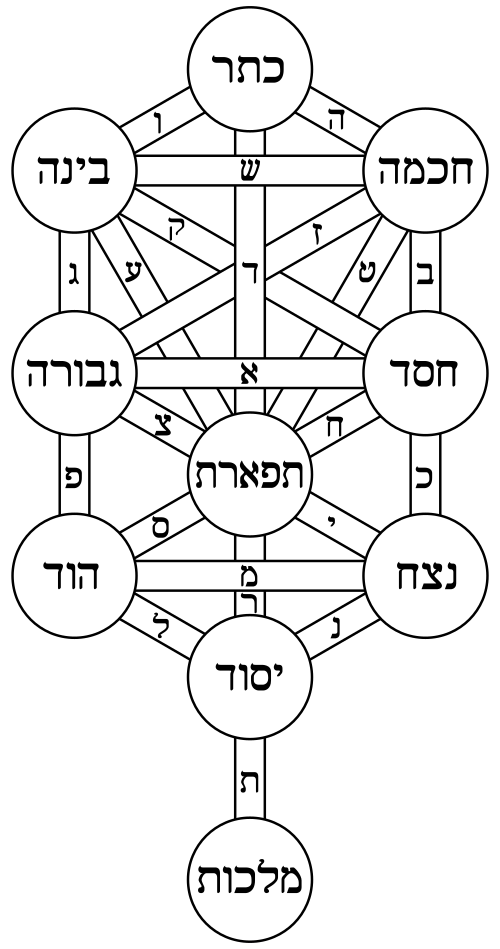

The Zohar’s Tiferet and Divine Unity: A Messianic Connection

The Zohar, compiled in the 13th century but attributed to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (2nd century CE), offers a mystical view of God’s unity through the Sefirot, with Tiferet (beauty) as the central “voice” of divine action. This resonates with Yeshua as the Logos, the Word who became flesh.

- The “Three Steps” Teaching: In Zohar II:43a–b (Parashat Yitro), Rabbi Abba teaches Rabbi Eleazar: “The mystery of the word YHVH: there are three steps, each existing by itself, yet they are one, and so united that one cannot be separated from the other. The Ancient Holy One is revealed with three heads, which are united into one” (The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, vol. 4, pp. 256–258). These “three steps” (likely Chochmah, Binah, and Tiferet) reflect a complex, inseparable unity in the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4, “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one”), not a simplistic “Adonai Echad.” This supports a divine unity compatible with Yeshua’s divinity.

- Tiferet as the Voice: Zohar I:22a calls Tiferet the “voice of God,” which “speaks from the heart of the divine” (Pritzker Edition, vol. 1, p. 133). This echoes Vayomer in Genesis 1 (e.g., “And God said, ‘Let there be light,’” Genesis 1:3), suggesting Tiferet as God’s creative Word.

- Messianic Role: Zohar III:65b links Tiferet to the Messiah: “The Messiah stands in Tiferet, the place of divine compassion, to redeem Israel” (Pritzker Edition, vol. 8, p. 367). While not explicitly divine, this positions the Messiah within God’s central emanation, aligning with Yeshua as the incarnate Word.

Messianic Jewish scholars see Tiferet as a bridge to Yeshua’s divinity:

- Joseph Shulam: In “Bava Batra: A Surprising Look at the Messiah in the Talmud” (Netivyah.org, 2020), Shulam argues that the Zohar’s mystical unity reflects ancient Jewish ideas of a divine Messiah, suppressed by later rabbis. He cites Zohar II:43a–b, suggesting its “three steps” parallel the Brit HaChadashah’s Trinity, with Tiferet as Yeshua’s divine role.

- Michael Brown: In Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus (vol. 2, p. 45, Baker Books, 2000), Brown connects Tiferet’s “voice” (Zohar I:22a) to John 1:1-3, arguing that the Zohar’s unity supports Yeshua as the creative Word. He cites Zohar III:65b to link the Messiah to Tiferet.

- David H. Stern: In Jewish New Testament Commentary (p. 131, Jewish New Testament Publications, 1992), Stern suggests the Zohar’s Tiferet echoes the Logos, referencing Zohar I:22a as evidence of a divine intermediary in Jewish thought, fulfilled by Yeshua.

The Zohar’s complex unity, while monotheistic, opens the door to Yeshua as the divine Tiferet incarnate, but it’s not the only ancient witness.

Ancient Jewish Sources: The Messiah as the Creative Word

The Brit HaChadashah declares, “In the beginning was the Word… All things were made through Him… And the Word became flesh” (John 1:1-3, 14, NKJV), tying Yeshua to Vayomer. Ancient Jewish texts from the Second Temple period (516 BCE–70 CE) support a divine Messiah as God’s creative agent, closer to Messianic beliefs than modern Orthodox Judaism.

Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE–50 CE):

- Text: In On the Creation of the World (24–25), Philo calls the Logos God’s “firstborn son” and “instrument” of creation: “The Logos is the image of God, by which the whole universe was framed” (Philo, Works, trans. F.H. Colson, Loeb Classical Library). In Questions and Answers on Genesis (1.4), he writes, “God spoke, and it was done, for the Logos is the agent of His will.”

- Messianic Scholar: David H. Stern (Jewish New Testament Commentary, p. 131) cites Philo’s Logos as a precursor to Yeshua, arguing that Vayomer in Genesis 1 aligns with John’s Word. Stern references On the Creation 24–25 to show Hellenistic Jewish openness to a divine intermediary.

- Significance: Philo’s Logos, contemporary with the Pharisees and Sadducees, supports Yeshua as the creative Word, though not explicitly a Messiah.

1 Enoch (Parables of Enoch, 37–71, 1st century BCE–CE):

- Text: The Parables of Enoch describe a pre-existent “Son of Man” involved in creation: “His name was named before the sun and the constellations were created” (1 Enoch 48:2-3) (The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, ed. James H. Charlesworth). He sits on God’s throne (1 Enoch 51:3, 62:7).

- Messianic Scholar: Michael Brown (Answering Jewish Objections, vol. 2, p. 45) cites 1 Enoch 48:2-3, arguing that the Son of Man’s pre-existence and divine role mirror Yeshua as the Logos. He connects this to Zohar I:22a’s Tiferet as the creative voice.

- Significance: The Son of Man’s role in creation aligns with Vayomer and John 1:1-3, showing Second Temple Jewish belief in a divine-like Messiah.

Dead Sea Scrolls (4Q246, “Son of God Scroll,” 1st century BCE):

- Text: 4Q246 calls a figure “Son of God” and “Son of the Most High,” with an “everlasting kingdom” (4Q246 II:5–7) (The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, trans. Geza Vermes). It echoes Daniel 7:13-14’s divine “Son of Man.”

- Messianic Scholar: Joseph Shulam (Netivyah.org, 2020) cites 4Q246, arguing it reflects a divine Messiah, akin to Yeshua, whose creative role parallels Tiferet (Zohar II:43a–b). He connects it to John 1:1-3.

- Significance: The Essene text suggests a divine-like figure, supporting a Messiah tied to God’s creative power.

Targum Neofiti (1st–4th century CE):

- Text: Genesis 1:1 in Targum Neofiti reads: “In the beginning, with wisdom [or ‘by the Word,’ Memra], the Lord created the heavens and the earth.” For Genesis 1:3, “And the Memra of the Lord said, ‘Let there be light’” (The Aramaic Bible, trans. Martin McNamara).

- Messianic Scholar: Arnold Fruchtenbaum (Ariel Ministries Commentaries, ariel.org) cites Targum Neofiti’s Memra as evidence of Yeshua as the creative Word, linking it to Vayomer and John 1:1-3. He argues the Memra reflects ancient Jewish thought suppressed by later rabbis.

- Significance: The Memra, used in synagogue readings, shows Pharisaic familiarity with a divine intermediary, aligning with Yeshua as the Logos.

These sources—Philo, 1 Enoch, 4Q246, and Targum Neofiti—reveal that ancient Jews, including Essenes and Hellenistic Jews, embraced divine intermediaries like the Logos or Memra, tied to Vayomer, supporting Yeshua’s identity as the Word incarnate.

Modern Orthodox Judaism: A Shift from Ancient Thought

Modern Orthodox Judaism, shaped by Rashi (1040–1105 CE) and Ramban (1194–1270 CE), insists on a human Messiah and strict monotheism, rejecting Yeshua’s divinity. This diverges from the diversity of Second Temple Judaism, where mystical ideas flourished. I believe this shift reflects a reaction to Christianity, not the ancient Pharisees or Sadducees.

Rashi and Ramban’s Views:

- Rashi: On Deuteronomy 6:4, Rashi defines echad as absolute singularity (Chumash with Rashi), countering Christian Trinitarianism. On Isaiah 53, he identifies the suffering servant as Israel, not a divine Messiah (Commentary on Isaiah), unlike earlier messianic readings (Targum Jonathan).

- Ramban: In Commentary on the Torah (Deuteronomy 6:4), Ramban rejects any divine division, opposing Christian claims. In the 1263 Disputation of Barcelona, he cites Sanhedrin 98a for a human Messiah (Disputation of Barcelona, trans. Chavel). On Genesis 1:1, he avoids linking Vayomer to a divine Messiah.

- Messianic Critique: Michael Brown (Answering Jewish Objections, vol. 2, p. 53) argues Rashi’s Isaiah 53 interpretation was a response to Christian apologetics, diverging from Targum Jonathan’s messianic view. Joseph Shulam (Netivyah.org) claims Ramban’s monotheism suppressed Memra concepts to counter Christianity.

Ancient Pharisaic and Sadducean Beliefs:

- Pharisees: The Talmud (Sanhedrin 98a–99a) describes a human Davidic Messiah, but Targum Neofiti’s Memra suggests openness to a divine intermediary in creation (The Aramaic Bible). Polemics against “Yeshu” (Sanhedrin 43a) deny divinity but reflect awareness of Christian claims (Jesus in the Talmud, Schäfer, 2007).

- Sadducees: Focused on the Torah, Sadducees likely rejected divine intermediaries (Josephus, Antiquities 18.1.4), but their limited messianic speculation doesn’t negate broader Second Temple diversity (War 2.8.14).

- Diversity: Texts like 1 Enoch, 4Q246, and Philo show Second Temple Jews embraced divine figures, unlike Rashi/Ramban’s strict monotheism. The Memra indicates Pharisaic exposure to such ideas, suppressed post-70 CE.

The Shift and Christian Influence:

- Historical Pressure: Christianity’s rise (4th century CE) and medieval persecutions (e.g., 1240 Disputation of Paris, 1263 Disputation of Barcelona) pushed rabbis to emphasize monotheism. David H. Stern (Jewish New Testament Commentary, p. 131) argues this led Rashi/Ramban to reject mystical concepts like the Memra or Logos, present in Targum Neofiti and Philo.

- Suppression of Mysticism: Arnold Fruchtenbaum (Ariel Ministries Commentaries) claims post-Temple rabbinic Judaism consolidated around peshat (plain meaning) to counter Christian and Gnostic influences (Sanhedrin 38b), sidelining 1 Enoch and Memra ideas (en.wikipedia.org, Jewish Encyclopedia).

- Ancient Continuity with Messianic Belief: Joseph Shulam (Netivyah.org) and Michael Brown (Answering Jewish Objections, vol. 2, p. 45) argue that 1 Enoch, 4Q246, and Targum Neofiti reflect Pharisaic-era openness to a divine Messiah, which Yeshua fulfills, unlike Rashi/Ramban’s human Messiah.

Conclusion

The Zohar’s Tiferet as the “voice of God” (I:22a) and “three steps” of divine unity (II:43a–b) align with Yeshua as the Logos who created all things and became flesh (John 1:1-14). Ancient sources—Philo’s Logos (On the Creation 24–25), 1 Enoch’s Son of Man (48:2-3), 4Q246’s Son of God, and Targum Neofiti’s Memra—show Second Temple Jews embraced a divine intermediary tied to Vayomer, supporting Messianic claims. Messianic scholars like Joseph Shulam, David H. Stern, Michael Brown, and Arnold Fruchtenbaum connect these to Yeshua, arguing that modern Orthodox Judaism’s rejection of a divine Messiah, as seen in Rashi and Ramban, diverges from ancient Pharisaic diversity due to Christian pressures. The Zohar and Second Temple texts reveal a vibrant Jewish theology that resonates with the Brit HaChadashah, affirming Yeshua as the divine Mashiach.

Sources and References:

- The Zohar, Pritzker Edition, trans. Daniel C. Matt, Stanford University Press, vol. 1, p. 133 (I:22a), vol. 4, pp. 256–258 (II:43a–b), vol. 8, p. 367 (III:65b).

- Philo of Alexandria, On the Creation of the World (24–25, 146–147), Questions and Answers on Genesis (1.4, 1.54), trans. F.H. Colson, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press.

- 1 Enoch (Parables of Enoch, 37–71), trans. E. Isaac, in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, ed. James H. Charlesworth, Doubleday, 1983.

- The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, trans. Geza Vermes, Penguin, 2011 (4Q246).

- Targum Neofiti, trans. Martin McNamara, The Aramaic Bible, Liturgical Press, 1992.

- Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 38b, 43a, 98a–99a, Avot 1, Shabbath 104b, trans. Soncino Press.

- Rashi, Commentary on Deuteronomy 6:4, Isaiah 53, in Chumash with Rashi, trans. A.M. Silbermann, Feldheim Publishers.

- Ramban (Nachmanides), Commentary on the Torah, Genesis 1:1, Deuteronomy 6:4, trans. Charles B. Chavel, Shilo Publishing.

- Disputation of Barcelona, trans. Charles B. Chavel, Shilo Publishing, 1983.

- Schäfer, Peter. Jesus in the Talmud. Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Brown, Michael. Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus, vol. 2, Baker Books, 2000.

- Stern, David H. Jewish New Testament Commentary, Jewish New Testament Publications, 1992.

- Shulam, Joseph. “Bava Batra: A Surprising Look at the Messiah in the Talmud,” Netivyah.org, 2020, https://netivyah.org.

- Fruchtenbaum, Arnold. Ariel Ministries Commentaries, https://ariel.org.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.1.3–4, Jewish War 2.8.14, trans. William Whiston.

- Jastrow, Marcus. A Dictionary of the Targumim, Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature, 1903.

- “Jewish Encyclopedia: Memra,” http://jewishencyclopedia.com.

Congratulations @linda2021! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 700 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPThe historical details and the sources are very complicated; not easy to follow.

!BBH

!PIZZA

!LOLZ

lolztoken.com

but then I turned myself around.

Credit: theabsolute

@linda2021, I sent you an $LOLZ on behalf of kopiko-blanca

(1/6)

NEW: Join LOLZ's Daily Earn and Burn Contest and win $LOLZ

$PIZZA slices delivered:

@kopiko-blanca(1/5) tipped @linda2021

Come get MOONed!