The Latin American Report # 545

The recently concluded ordinary parliamentary session left two hot-button issues. I previously addressed one in an earlier report, concerning a counterproductive and objectively unnecessary statement by the then Minister of Labor and Social Security, who brazenly and with impunity attempted to sweep under the rug, in broad daylight, serious social problems, such as growing mendicancy. While I don't rule out that she might have landed herself in that predicament alone, I am convinced she had already floated this absurd narrative that "there are no beggars in Cuba"—only people disguised as such—in other forums attended by the leader of the ruling Communist Party himself.

Indeed, I don't rule out that her battered speech conveyed an opinion generated by the country's highest political leadership. In Cuba's highly controlled political system, it's highly unlikely for a minister or any official to publicly defend a policy—with specific arguments—without the entire presentation having been previously vetted by various political and governmental power structures. In any case, the result was her dismissal within 48 hours, following widespread rejection across the entire Cuban political spectrum, with many opportunists seizing a golden chance to lambast the political establishment, albeit with little sincere concern for the critical situation faced by the most vulnerable today. Whether the now former minister ended up as a scapegoat or was rightly dismissed for expressing a non-consensual view, history will tell.

But just as the ordinary session of the officially named National Assembly of People's Power—which meets in plenary only twice a year—was concluding, the Council of State—a smaller, operational body derived from it and that represents it between plenary sessions—surprised everyone by introducing a bill to reform the very Constitution. Specifically, it targeted a requirement preventing people over sixty from being considered for the position of President of the Republic.

A first problem here is that constitutions should have a certain degree of stability over time, and Cuba's current one is only six years old. Furthermore, while it's true that a sudden change in context or socio-political dynamics can sometimes force changes to legislation, even something as sensitive as the constitution, the argument invoked this time is unsustainable. Both in the initial imposition of the age restriction for assuming the office—for which only one candidate is proposed and is voted on, or rather ratified, by Parliament—and now in its removal, the decisive criterion has been that of Army General and historic leader of the Cuban Revolution, Raúl Castro.

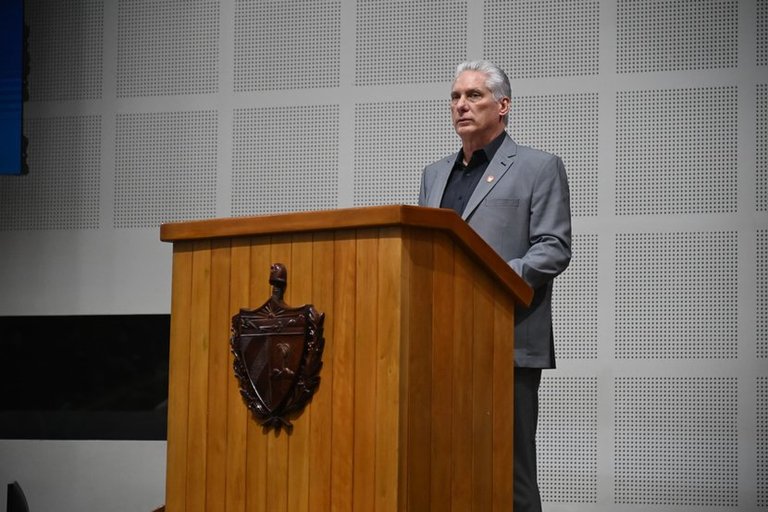

Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez is the Cuban current president (source of the image).

Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez is the Cuban current president (source of the image).Fidel Castro's younger brother, at various points during the past decade, urged the adoption of both the 60-year age limit for holding top political and state positions, and also the two-term limit for them, including those of First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and President of the Republic. Although the population vigorously debated the establishment of age limits, the Cuban constituents, clearly influenced or constrained by Raúl's stance, ended up accepting it unanimously, and then, the People, ratified it in a referendum.

These changes were defended first as a search for young blood, but also by citing certain experiences from other historical events, like the deaths of three top leaders of the Soviet Communist Party within a short timeframe. Or as part of an attempt to project greater "institutionalization"—which I translate as a way to better market the Cuban political system to the world.

Now, literally, I agree with the decision—adopted by a historically passive Congress, regardless of its composition, which rarely rejects a proposal put before it—to now remove this self-imposed constitutional restriction in 2019. I believe it should be a rigorous, comprehensive analysis of each candidate that determines whether a person can hold this or any other office, or generally contribute to society, regardless of their age. Age itself should not be the factor, but rather the biological dynamics we tend to associate with the relentless passage of time, such as our physical or intellectual capacity.

What I criticize here is the poor political engineering that leads to modifying an important aspect of the Magna Carta after only six years, and above all, doing so by invoking the flimsy argument of "population aging." This is a problem that has been discussed in Cuba for a long time, even well before the current constitution was approved in 2019. Everything indicates there was very poor political calculation back then, failing to project whether there would be suitable reserves to succeed the current President of the Republic when the time came—a position which, moreover, is just one post. General population aging can never be a sufficient reason to change a provision affecting only one position.

It remains to be seen whether the two-term presidential limit will be sustained. Changing it, moreover, legally requires a referendum. That would be an even cruder move than the current one, as it would firmly cement the plausible argument that the political establishment modifies something as sacred as the Constitution when it finds it convenient.

Source

Source

Posted Using INLEO

Congratulations @limonta! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP