The Hard Trade-offs of Migration: Some ideas from my Cuban perspective

Worked with Canva AI, source here.

Worked with Canva AI, source here.As we already know, migration is deeply rooted in human history. In the Cuban case—the specific focus of this piece—it’s worth remembering that in the three years prior to the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, the number of Cuban immigrants in the United States doubled compared to the 1951–1955 period. During that timeframe, figures as diverse as the legendary master drummer Chano Pozo and the parents of Marco Rubio—the current Foggy Bottom's head—arrived to live the "American Dream."

After 1959, we’ve witnessed the weaponization of migration from both ends of the U.S.-Cuba conflict. Cubans receive preferential, VIP treatment in the U.S. immigration system. The dissonance between Havana and Washington has led to a series of historic crises: for example, the 1980 Mariel boatlift or the 1994 balseros (rafters) crisis. At one point, there was even a crazy mechanism known as the "wet foot, dry foot" policy, which meant that if Cuban rafters touched U.S. soil, they were almost automatically paroled and could later apply for the Cuban Adjustment Act; those intercepted at sea were returned to the island.

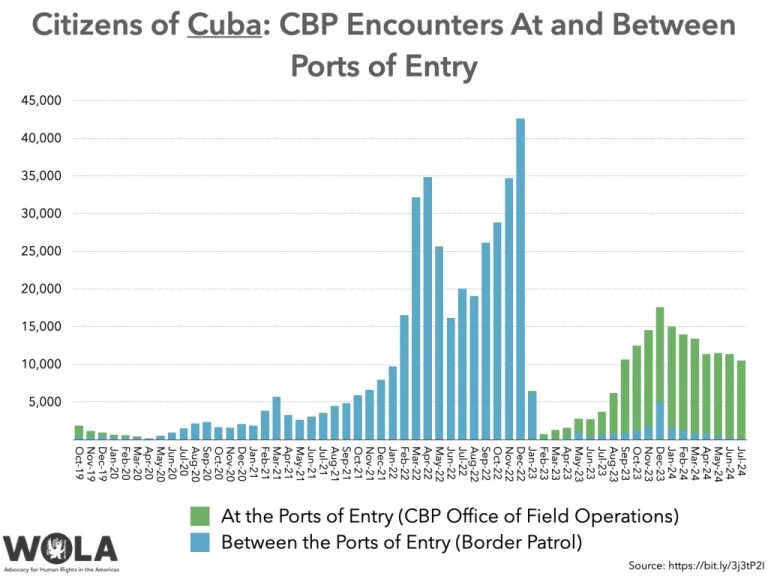

In recent years, up until Donald Trump’s return to power, tens of thousands of Cubans crossed the U.S.-Mexico border or flew directly to the United States—largely taking advantage of two Biden administration programs. We’re talking record numbers: an estimated 850,000 Cubans arrived in the U.S. between 2022 and September 2024. All this unfolded amid a national nightmare whose causes aren’t the focus here. What I want to share with you, as the title of this post suggests, are some of the hard trade-offs that migration entails in the current context, particularly from a family perspective. Below, I paint a picture based on real-life experiences of relatives and friends on both sides of the Florida Strait.

Source

SourceThey want us here

From what I observe, the grandparents and parents left behind are the primary victims here. They’ve had to smile as they bid farewell to their grandchildren, sons and daughters, letting them believe they aren’t shattered inside, yet feeling their absence from the very moment the idea of emigrating takes shape. They don’t want them trapped in our insurmountable crisis, but it pains them that their only contact will be through a screen, that they won't be able to hold their grandchildren or take them to the park for a long time. Take the parents of L., my childhood best friend. They have never cradled their six-year-old granddaughter, when these are precious, irreplaceable moments.

Those on the other side—whether in Miami or Madrid—might argue their presence abroad is critical to support their families, to care of them. Thanks to their work there, their parents and grandparents can eat and dress with some dignity. If medicine runs short, they’re the ones who can cope with the absurd domestic inflation, where even dreams are expensive. And those here know full well that’s true. But I know—because I see and feel it—that many would choose a thousand times over to have them seated at the table, maybe sharing a not-so-great meal, but together. No remittance in the world can fill the void I nearly touch in some relatives and other people. I live about 15 hours (by road) from my hometown. But I am able to go at least three or four times a year, so my mother can touch her grandson’s face, feed him, and take him out for a walk. It is very different when the sea becomes your border.

I have a friend with all the money in the world to leave wherever he pleases, but he always asks himself: What if my mother needs me, and I’m not here? That dilemma hits home in a current, deeply personal case that made me reflect on this issue. A woman is lying in bed with a critical condition, but her sons and daughters live abroad. You see, thanks to them, she’s had food, medicine, even an electric generator to endure the island’s inhumane, hours-long blackouts. Yet right now, I believe the only thing that could lift her from that bed is if at least one of them walked through the door of her hospital cubicle and held her hand. So, the youngest will fly tomorrow—and she won’t ever want to let her go again.

Worked with Canva AI, source here.

Worked with Canva AI, source here.

Sending you some Ecency curation votes!

Thanks for this support. Best regards from Havana.

My pleasure

!INDEED