Among numbers lies a hidden order, waiting to be revealed II - Entre los números se esconde un orden oculto, esperando ser revelado II [ENG-ESP]

The key distinction of the Sieve of Eratosthenes compared to the previous approach, which checks divisibility by each prime number, is that it identifies the multiples of prime numbers. These multiples are generated through successive additions starting from the prime itself, with a constant difference between them equal to that prime number.

La distinción clave de la Criba de Eratóstenes respecto del enfoque anterior, que comprueba la divisibilidad por cada uno de los números primos, es la de hallar los múltiplos de estos. Estos múltiplos son generados mediante sumas sucesivas a partir del propio primo, con una diferencia constante entre ellos que es igual al número primo en cuestión.

Eratosthenes approach - El enfoque de Eratóstenes

Starting with 2, the first prime number, we cross out all of its multiples up to n, which is the limit of our list. A multiple of a number is one that contains it an exact number of times. For example, 25 contains 5 exactly five times, therefore 25 is a multiple of 5. The multiples of a number k are obtained by multiplying k by each of the natural numbers. Once we cross them all out, the next number we encounter in the list will be the next prime: 3. This means that a set containing that many elements cannot be evenly divided into groups of 2 (or, in other words, 3 is not a multiple of 2), but only into groups of 1 or 3 —which is precisely the definition of a prime number.

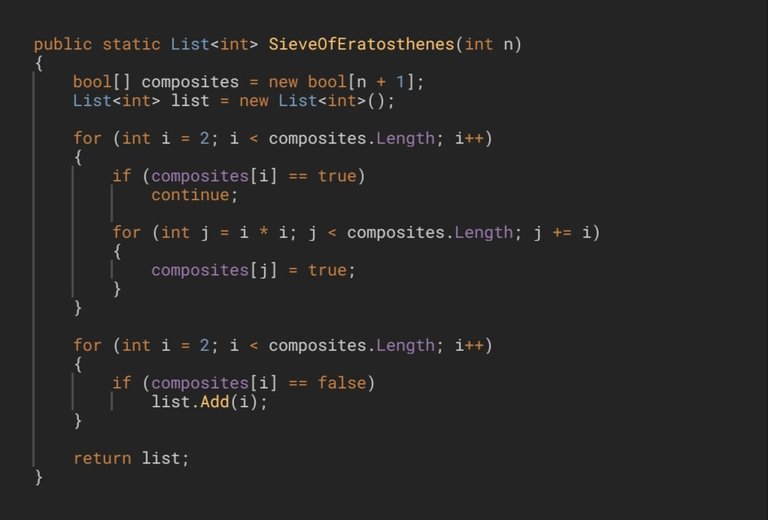

As in the first two versions, we will create a boolean array and make use of the indices of each of its elements to our advantage. If any element has already been marked as true, there is no need to enter the inner loop, since we know the number is composite and therefore all its multiples will also be marked as such. The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic tells us that every positive integer greater than 1 is either a prime number or can be factored into a product of primes. If a number is a multiple of some composite number, that means they will share at least one prime factor in common. Thus, it is unnecessary to check it again, because we can be completely sure it is already marked as true.

The iterator variable of the inner loop will be initialized at the first multiple (greater than the number itself, of course) of the current prime (int j = i + i), and with each loop iteration we will keep marking all of its multiples as true. The loop variable will grow in steps equal to that prime value, precisely to reach all of its multiples. Finally, we return the list with the prime numbers between 2 and n.

Comenzando por el 2, que es el primer número primo, vamos a tachar todos sus múltiplos hasta llegar a n, que es el límite de nuestra lista. El múltiplo de un número es aquel que lo contiene un número exacto de veces. Por ejemplo, 25 contiene a 5 una cantidad exacta de 5 veces, por lo tanto 25 es un múltiplo de 5. Los múltiplos de un número k se obtienen al multiplicar k por cada uno de los números naturales. Una vez tachados todos, el siguiente número que encontremos en la lista será el siguiente número primo: el 3. Esto quiere decir que un conjunto que contiene dicha cantidad de elementos, no se puede repartir de manera equitativa en grupos de a 2 (o que 3 no es un múltiplo de 2), sólo en grupos de a 1 o de a 3 —qué es precisamente la definición de número primo.

Al igual que en las primeras 2 versiones, crearemos un array de booleanos y utilizaremos los índices de cada uno de sus elementos a nuestro favor. Si alguno de los elementos ha sido marcado comotrue, no necesitamos entrar al bucle interno, ya que sabemos que el número es compuesto y, por lo tanto, todos sus múltiplos también estarán marcados como tal. El Teorema Fundamental de la Aritmética nos dice que todo número entero positivo mayor que 1 es un número primo o puede ser descompuesto en un producto de números primos. Si un número es múltiplo de algún número compuesto, eso significa que ambos tendrán en común, al menos, un mismo factor primo, por lo que es innecesario volverlo a comprobar ya que sabremos con toda seguridad que está previamente marcado comotrue.

La variable iteradora del bucle interno la inicializaremos en el primer múltiplo (mayor que el propio número, por supuesto) del número primo actual (int j = i + i) y, a cada vuelta de bucle, iremos marcando todos sus múltiplos comotrue. La variable del bucle irá creciendo a un ritmo igual a ese valor primo, precisamente para dar con todos sus múltiplos. Finalmente devolveremos la lista con los números primos que se encuentran entre 2 y n.

Let's improve the sieve - Mejoremos la criba

This version also works well and gives us the result we are looking for, but let’s see how we can improve it to make it more efficient. One way to enhance our algorithm is by realizing that it is not necessary to start crossing out composite numbers from the very first multiple. If we think about it, the first multiple of each prime number is also a multiple of 2, since it is obtained by adding the prime number to itself —that is, multiplying it by 2. So should we start from the second multiple instead? Well, the second multiple is the result of multiplying by 3, which means we would be making the same mistake.

So where should we start then? Let’s take the number 11 as an example. It is not necessary to begin from its first multiple, since that multiple is also divisible by 2 and is already marked as composite. Nor is its second multiple, since it is divisible by 3. Neither is the third, as it is divisible by 4, which in turn is a multiple of 2, so it would have been marked as composite from the start. If we keep following this reasoning, we realize that all the numbers obtained by multiplying 11 by any of the preceding numbers will have already been eliminated, and we would just be executing unnecessary steps in our algorithm.

But 11 × 11 has not yet been marked, since the only prime factor of 121 is 11 itself. Therefore, multiplying a prime number by itself (or squaring it) means that this multiple shares no prime factors with any of the preceding numbers, which implies that it has not been marked yet as composite. So, instead of initializing the variable of the inner loop at i + i, we will initialize it at i * i.

Esta versión también funciona bien, y nos da el resultado que buscamos, pero veámos como podemos mejorarla para que sea más eficiente. Una primera forma de mejorar nuestro algoritmo es percatándonos de que no es necesario comenzar a tachar los números compuestos a partir del primer múltiplo. Si lo pensamos, el primer múltiplo de cada número primo es también múltiplo de 2, ya que se obtiene de sumar el número primo consigo mismo, es decir, multiplicarlo por 2 ¿Entonces comenzamos a partir del segundo múltiplo? Bueno, el segundo múltiplo es el resultado de multiplicar por 3, así que estaríamos cometiendo el mismo error.

¿A partir de donde empezamos entonces? Pensemos en el número 11, por ejemplo. No es necesario comenzar a partir de su primer múltiplo, ya que también es múltiplo de 2 y está previamente marcado como compuesto. Tampoco su segundo múltiplo, ya que es múltiplo de 3. Tampoco el tercero, pues es múltiplo de 4, que a su vez es múltiplo de 2, por lo que estará marcado como compuesto desde el inicio. Si seguimos haciendo esto nos daremos cuenta de que, todos los números que se obtienen de multiplicar 11 por cada uno de los números que le anteceden, estarán eliminados previamente, y que estaremos ejecutando pasos innecesarios en nuestro algoritmo.

Pero 11 x 11 no ha sido marcado previamente, ya que el único factor primo que tiene 121 es precisamente 11. Por tanto, multiplicar un número primo por sí mismo (o elevarlo al cuadrado) equivale a decir que dicho múltiplo no tiene factores primos en común con ninguno de los números previos, lo cual significa que no está marcado aún como compuesto. Así que, en lugar de inicializar la variable del bucle interior eni + i, la inicializaremos eni * i.

Another improvement to the Sieve is to set the stopping condition of the outer loop at the square root of n. Why do we do this? For a simple reason: if we agree that we will begin marking the multiples of i as composite starting from i * i, and the result of i * i turns out to be greater than n, that means there is nothing left to check and that we have already marked all the composite numbers as true.

En otra mejora de la Criba, establecemos la condición de parada del bucle externo en la raíz cuadrada de n ¿Por qué hacemos esto? Por una sencilla razón: si convenimos en qué vamos a comenzar a marcar como compuestos los múltiplos de

ia partir dei * i, y el resultado de calculari * iresulta ser mayor que n, eso significa que no hay más nada que buscar y que habremos marcado todos los números compuestos como verdaderos.

English translation made with DeeplTranslate

Traducción al inglés hecha con DeeplTranslate