Among numbers lies a hidden order, waiting to be revealed I - Entre los números se esconde un orden oculto, esperando ser revelado I [ENG-ESP]

¿What in the world is a sieve ? - ¿Qué se supone que sea una criba ?

A sieve is a mesh, or any perforated surface, whose purpose is to allow us to filter out everything we do not want. It makes no difference whether it is in the kitchen to sift flour, in agriculture to separate the grain from the chaff, or in construction to distinguish sand from stones —the principle is exactly the same: let the small pass through and retain the large. It is a process of purification.

Throughout history, prime numbers have fascinated both mathematicians and amateurs alike, because they seem to conceal an order we never manage to decipher —as if they held a secret that resists being revealed. When we analyze them, we are unable to find a pattern or a relationship among them that would allow us to obtain them right away. In other words, there is no magic formula that enables us to generate them instantaneously; it is impossible to predict when the next one will appear. Moreover, despite being infinite, they are relatively scarce compared to the entirety of natural numbers, and as we move further along the number line, it becomes increasingly difficult to come across one of them.

What would happen if we applied the same principle of “sieving” to the world of mathematics? What if we could “sieve” or “filter” a list of numbers, removing all those that are not prime and leaving only those that truly are? More than 2,000 years ago, the Greek mathematician and great librarian of Alexandria, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, devised precisely a method to achieve this: a sequence of steps, an elegant algorithm that allowed him to find all the prime numbers smaller than a certain number n —what we now know as the Sieve of Eratosthenes. It is called a “sieve” because, as if it were a perforated surface, it performs a series of successive filtrations that eliminate the composite numbers from the list, refining it and revealing which numbers are prime and which are not.

Una criba es una malla, o cualquier superficie perforada, cuyo propósito es el de permitirnos filtrar todo aquello que no deseamos. No importa si es en la cocina para tamizar la harina, en la agricultura para separar el grano de la paja, o en la construcción para diferenciar la arena de las piedras —el principio es exactamente el mismo: dejar pasar lo pequeño y retener lo grande. Es un proceso de depuración.

A lo largo de la historia, los números primos han fascinado a matemáticos y a aficionados por igual, porque parecen esconder un orden que nunca terminamos de descifrar —como si guardaran un secreto que se resiste a ser revelado. Cuando los analizamos, no somos capaces de encontrar un patrón, o una relación entre ellos, de manera que podamos obtenerlos de inmediato. Es decir, no existe una fórmula mágica que nos permita generarlos instantáneamente; es imposible prever cuando aparecerá el siguiente. Además, a pesar de ser infinitos, son muy pocos, si los comparamos con la totalidad de los números naturales y, a medida que vamos avanzando por la recta numérica, se nos hace cada vez más difícil dar con alguno de ellos.

¿Qué pasaría si aplicáramos el mismo principio de "cribado" al mundo de las matemáticas? ¿Qué pasaría si pudiésemos "cribar" o "tamizar" una lista de números, eliminando todos aquellos que no son primos y dejando sólo a los que sí lo son? Hace más de 2000 años, el matemático griego y gran bibliotecario de Alejandría, Eratóstenes de Cirene, ideó precisamente un método para lograr esto: una serie de pasos, un algoritmo elegante que le permitía encontrar todos los números primos menores que un cierto número n —lo que hoy conocemos como la Criba de Eratóstenes. Se le llama "criba" porque, como si de una superficie perforada se tratase, realiza una serie de filtrados sucesivos que eliminan a los números compuestos de la lista, depurándola y revelando quienes son primos y quienes no.

A first approach - Un primer enfoque

Let’s begin with the definition of a prime number. A prime number is one that is divisible only by 1 and itself. In other words: given a set of n elements, if we want to divide them evenly, we can only do so in n groups of 1 element each, or in a single group of n elements.

This, however, is not a sufficient condition to determine whether a number is prime, since every number trivially satisfies it. What we really need to check is whether the number is divisible by any other number besides 1 and itself.

Therefore, a first intuitive approach to tackle the problem could be: test whether n is divisible by any of the numbers in the range [2, n − 1]. If none divides it exactly (with zero remainder), then n is prime. Put another way: each time we encounter a new number that hasn’t been crossed out from the list, it means none of the previous ones was able to divide it evenly.

Primero comencemos con la definición de número primo. Un número primo es aquel que sólo es divisible por 1 y por sí mismo. En otras palabras: dado un conjunto de n elementos, si queremos repartirlos de manera equitativa, sólo podremos hacerlo en n grupos de a 1 o en 1 solo grupo de n elementos.

Lo anterior no es condición para comprobar si un número es o no primo, ya que todos los números cumplen con esta condición trivial. Lo que debemos comprobar en su lugar es si dicho número es divisible por algún otro número, aparte de 1 y el propio número.

Por lo tanto, una primera intuición para abordar este problema podría ser: revisar si n es divisible por alguno de los números en el rango [2, n - 1]. Si ninguno logra dividirlo exactamente (sin dejar resto), entonces n es primo. Dicho de otro modo: cada vez que nos encontremos con un nuevo número sin tachar dentro de la lista, eso significará que ninguno de los anteriores fue capaz de dividirlo y de arrojar resto 0 en el proceso.

The algorithm - El algoritmo

To run the algorithm, we first need to build a table or a list with all the natural numbers between 2 and n. It’s not necessary to literally construct a list or an array of numbers; we can take advantage of indexing to obtain the sequence implicitly.

In this case, we’ll use a boolean array, which we’ll call composites. We’ll rely on the default value of boolean variables (namely false) and assume that all elements are prime until proven otherwise.

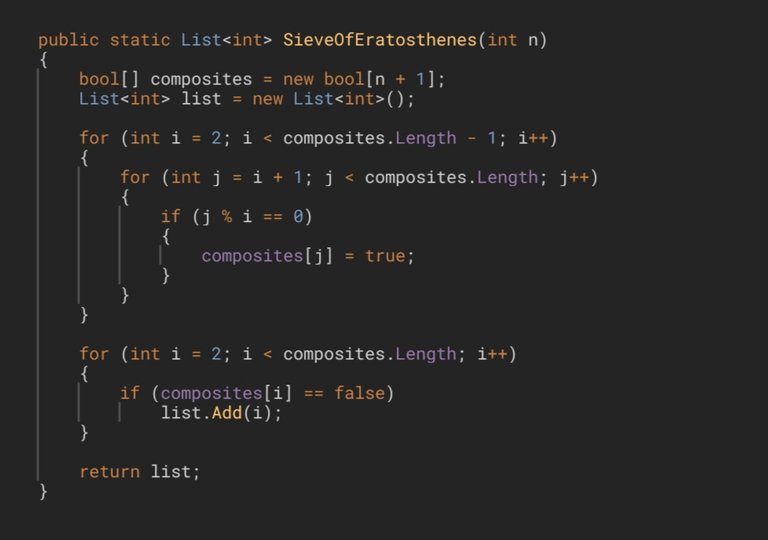

In a first version, the iterator of the outer loop will be initialized at 2. This means we’ll check the divisibility of each subsequent number by 2 and, if divisible, we’ll mark it as true. To avoid checking whether each element is divisible by more than one number —which is completely unnecessary— we’ll add a condition so that divisibility is only tested if the element has not yet been marked as composite, i.e., if it is still false. Once the outer loop has finished, the numbers that remain marked as false will be the primes (except for 0 and 1, which we already know are not prime). We’ll add them to a list and return it.

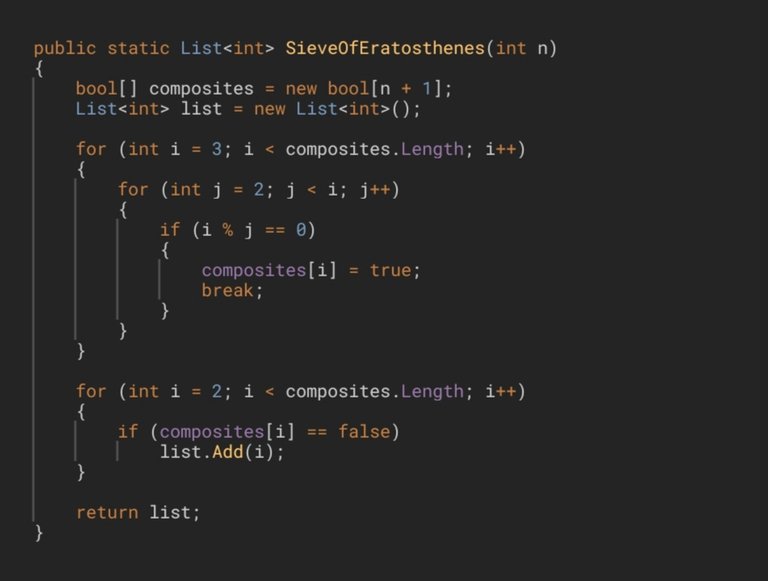

In a second version, we’ll do the same thing but in reverse. In this case, we’ll start the outer loop at 3 and the inner loop at 2. This means we’ll check whether each number is divisible by any of its predecessors and, if so, we’ll mark it as true, immediately exit the inner loop, and move on to the next iteration of the outer loop. Once all the composite numbers have been marked, we’ll add the primes to a list and return it.

Para ejecutar el algoritmo, primero necesitamos elaborar un tabla, o una lista, con todos los números naturales que están comprendidos entre 2 y n. No es necesario elaborar una lista literalmente, o un array de números; podemos aprovechar la capacidad de indexado de ambos para obtener la lista de números implícitamente.

En este caso utilizaremos un array de booleanos, al que llamaremoscomposites. Aprovecharemos el valor por defecto de las variables booleanas (o seafalse) y asumiremos que todos los elementos son primos hasta que se demuestre lo contrario.

En una primera versión, la variable iteradora del bucle externo será inicializada en 2, lo que significará que comprobaremos la divisibilidad de cada uno de los números siguientes por 2 y, en caso de ser divisibles, vamos a marcarlos comotrue. Para evitar tener que comprobar que cada elemento es divisible por más de un número –lo cual es completamente innecesario– agregaremos una condición para comprobar la divisibilidad sólo en caso de que el elemento no haya sido marcado como compuesto, es decir, en caso de que aún seafalse. Una vez terminemos de recorrer el bucle externo, quedarán marcados comofalselos números primos (exceptuando al 0 y al 1, que sabemos que no lo son). Los añadiremos a una lista y los devolveremos.

En una segunda versión, haremos lo mismo pero a la inversa. En este caso comenzaremos el bucle externo en 3, y el interno a partir de 2. Esto significa que comprobaremos si cada número es divisible por alguno de los números que lo preceden y, en ese caso, lo marcaremos comotrue, saldremos inmediatamente del bucle interno e iremos a la siguiente iteración del bucle externo. Una vez marcados todos los números compuestos, agregaremos los primos a una lista y la devolveremos.

This approach, while valid, is not the one used by the Sieve of Eratosthenes, but we will see this in the next post.

Esta manera de proceder, aunque válida, no es la que utiliza la Criba de Eratóstenes, pero eso lo veremos en el siguiente post.

English translation made with DeeplTranslate

Traducción al inglés hecha con DeeplTranslate