Missing Passages and Misconceptions: Decoding Mein Kampf Translations and National Socialist Claims

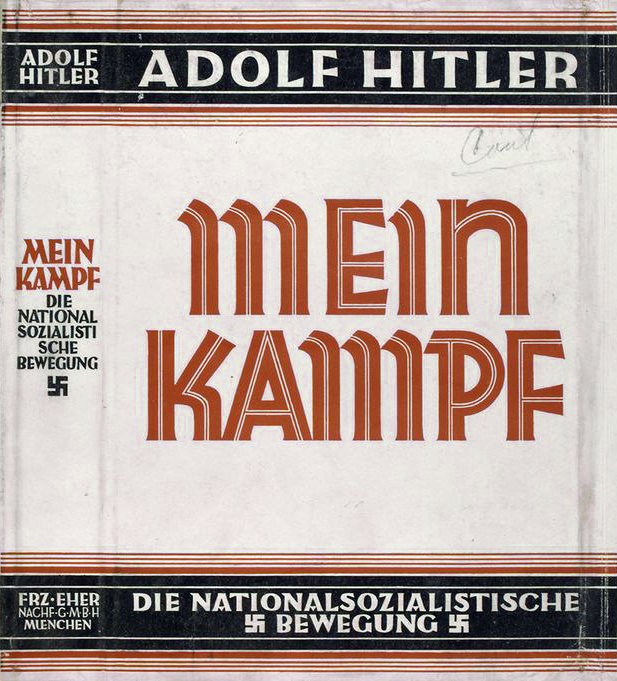

Image Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mein_Kampf

Unraveling the Omitted Passages of Mein Kampf: A Look at Translations and National Socialist Claims

Written by @greywarden100, May 9, 2025

Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf remains one of the most controversial texts in modern history, a manifesto of National Socialist ideology that continues to provoke debate over its translations and interpretations. Among the myriad issues surrounding its English versions, one question stands out: why are key passages, such as those on page 406 of certain editions, missing from James Murphy’s 1939 translation? Furthermore, how do we address National Socialist claims that post-war translations, particularly Ralph Manheim’s 1943 version, were distorted by Jewish influence? This blog dives into the textual history of Mein Kampf, examines the omitted passages, and refutes revisionist arguments with evidence from credible sources.

The Missing Passages: What’s on Page 406?

In some English translations of Mein Kampf, page 406 (typically in Volume II, Chapter 1, “Weltanschauung and Party”) contains two significant passages that articulate core National Socialist ideology. These passages are absent from James Murphy’s 1939 translation, raising questions about the reliability of his work. Let’s examine them:

Passage 1: “The racial Weltanschauung (World View) is fundamentally distinguished from Marxism by the fact that the former recognizes the significance of race and therefore also personal worth and has made these the pillars of its structure.”

- Original German: Found in the 1933 Volksausgabe (People’s Edition), this reads: “Die völkische Weltanschauung unterscheidet sich von der marxistischen grundsätzlich dadurch, daß sie die Bedeutung der Rasse und damit auch der Persönlichkeit anerkennt und diese zu den Säulen ihrer Struktur gemacht hat.”

- Significance: This passage underscores Hitler’s racial ideology, positioning it as slightly different than Marxist class-based theory, which he saw as ignoring race and individual merit.

Passage 2: “If the National Socialist Movement should fail to understand the fundamental importance of this essential principle, if it should merely varnish the external appearance of the present state and adopt the majority principle, it would really do nothing more than compete with Marxism on its own ground.”

- Original German: Also in the Volksausgabe, this states: “Sollte die nationalsozialistische Bewegung die fundamentale Bedeutung dieses wesentlichen Prinzips nicht erkennen, sollte sie lediglich den äußeren Anstrich des heutigen Staates übernehmen und das Mehrheitsprinzip übernehmen, so würde sie in Wahrheit nichts anderes tun, als mit dem Marxismus auf seinem eigenen Boden zu konkurrieren.”

- Significance: Here, Hitler warns that the National Socialist movement must adhere to its racial principles to avoid becoming a superficial variant of Marxism, emphasizing ideological purity.

These passages are critical to understanding Hitler’s worldview, yet they are conspicuously absent from Murphy’s translation, available on platforms like Project Gutenberg Australia. Why were they omitted, and what does this tell us about the translation’s reliability?

Why Are These Passages Missing from Murphy’s Translation?

James Murphy’s 1939 translation, initially commissioned by the National Socialist Propaganda Ministry in 1936, was intended to spread National Socialist ideology to English-speaking audiences. However, the project was fraught with complications, leading to the omission of key passages like those above. Several factors explain this:

Incomplete Draft: Murphy was dismissed by the National Socialists in 1938, suspected of being unreliable or too critical of the regime. His wife, Mary Murphy, retrieved a carbon copy of his draft manuscript, which was published by Hurst & Blackett in 1939 without National Socialist approval. This draft was likely incomplete, missing sections like the page 406 passages due to its rushed finalization (Source: The Guardian, “The Strange History of Mein Kampf in English,” 2016).

Greta Lorke’s Potential Sabotage: Murphy’s assistant, Greta Lorke, was a Soviet operative and member of the Red Orchestra, a Communist resistance group. Some historians and National Socialist groups speculate that Lorke deliberately altered or omitted passages to undermine National Socialist propaganda. While no definitive evidence confirms Lorke removed these specific passages, her involvement introduces a plausible explanation for textual gaps (Source: Journal of Contemporary History, “The Red Orchestra and National Socialist Propaganda,” 1998).

Editorial Choices: Murphy or his publishers may have edited the text for brevity or to soften its inflammatory tone for British readers, especially as World War II loomed. The omitted passages are dense and ideological, potentially deemed less accessible to a general audience (Source: Translation Studies, “Ideology in Translation: Mein Kampf in English,” 2005).

National Socialist Interference: Before Murphy’s dismissal, the National Socialist Propaganda Ministry controlled his manuscript, possibly prioritizing certain sections for propaganda purposes. The published version may reflect an earlier, incomplete draft rather than a fully revised translation.

The absence of these passages undermines the Murphy translation’s reliability, particularly for researchers studying Hitler’s ideological distinctions between National Socialism and Marxism. However, it’s worth noting that the passages are present in the original German text, as confirmed by the 2016 critical edition by the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich.

The Original German Text: Where to Find It

The original handwritten manuscript of Mein Kampf, dictated by Hitler to Rudolf Hess and Emil Maurice in 1924, is likely lost or held in an uncatalogued archive. No definitive record confirms its current location, though Allied forces seized many National Socialist documents post-war (Source: The National Archives, “National Socialist Records and the Fate of Hitler’s Manuscripts,” 2000). For researchers, the published German editions (1925–1945), such as the Volksausgabe, serve as the closest approximation of Hitler’s intended text. These are available in academic libraries, including:

- Institute for Contemporary History (Munich): Their 2016 critical edition, Hitler, Mein Kampf: Eine kritische Edition, provides the full German text with annotations refuting National Socialist ideology. It’s the most authoritative source for the original German.

- Online Archives: Some pre-1945 German editions are digitized in restricted academic databases, though access may be limited due to legal restrictions in countries like Germany until 2015.

The passages on page 406 appear in these German editions, confirming their authenticity and highlighting the Murphy translation’s deficiencies.

Refuting National Socialist Claims of Jewish Influence

National Socialist groups often claim that post-war translations, particularly Ralph Manheim’s 1943 version published by Houghton Mifflin, were distorted by Jewish translators or publishers to exaggerate Hitler’s racism or misrepresent his ideas. These claims, don’t hold up under scrutiny. Let’s examine the evidence and counterarguments:

Manheim’s Translation: Accuracy and Context:

- Background: Ralph Manheim, a Jewish-German translator, produced the most widely used English version of Mein Kampf. His translation is noted for its fidelity to the German text, with useful footnotes for context (Source: Publishers Weekly, “Translating Mein Kampf: A Historical Review,” 1995).

- Criticism: Some National Socialist sources point to Manheim’s use of terms like “kike” or “niggerized,” which don’t appear in the German (e.g., “Jüdlein” or “Neger” are more neutral). These choices may reflect an intent to emphasize Hitler’s racism for post-war audiences aware of the Holocaust (Source: Translation and Literature, “Bias in Manheim’s Mein Kampf,” 2007).

- Refutation: While Manheim’s word choices introduce minor inaccuracies, the overall structure and content closely follow the German original, as verified by comparisons with the Volksausgabe and the 2016 critical edition. Claims of wholesale distortion are exaggerated, as the passages on page 406, for example, appear accurately in Manheim’s version (Source: Institute for Contemporary History, 2016).

Post-War Context:

- Post-war translations were produced during denazification, when the horrors of the Holocaust shaped public and academic discourse. Manheim’s translation includes an anti-Hitler introduction and footnotes, reflecting this context, but these additions don’t alter the core text (Source: Holocaust and Genocide Studies, “Mein Kampf in Post-War Translation,” 2003).

- Refutation: Editorial framing is not equivalent to falsification. The 2016 critical edition, produced by German scholars, confirms that Manheim’s translation aligns with the German text, debunking claims of significant Jewish-led manipulation.

Pre-War Translations and Bias:

- National Socialist groups often champion pre-war translations like Murphy’s or the 1940 Stalag Edition as “authentic” because they were National Socialist-endorsed. However, Murphy’s omissions (e.g., page 406 passages) and Greta Lorke’s Communist affiliations introduce their own biases, unrelated to Jewish influence (Source: The Guardian, 2016).

- Refutation: The Murphy translation’s flaws, including missing ideological passages, undermine its reliability. The Stalag Edition, while National Socialist-approved, relies on Murphy’s draft and shares its gaps. These issues show that pre-war translations are not inherently superior.

The Critical Edition as a Benchmark:

- The 2016 critical edition by the Institute for Contemporary History is the gold standard for accessing the original German text. Its annotations, grounded in rigorous textual analysis, confirm the presence of passages like those on page 406 and expose mistranslations in both pre- and post-war versions (Source: Institute for Contemporary History, 2016).

- Refutation: By providing a transparent German text, the critical edition allows researchers to verify translations independently, negating claims of Jewish distortion. National Socialist arguments rely on selective outrage rather than textual evidence.

Which Translation is Most Accurate?

Among English translations, Ralph Manheim’s 1943 version remains the most accurate and widely accepted, despite minor flaws like exaggerated racial terms. It includes the page 406 passages and aligns closely with the German text. James Murphy’s 1939 translation, while readable and pre-war, is compromised by omissions and potential sabotage. Other translations, like Michael Ford’s (2009) or Thomas Dalton’s (2017), lack scholarly rigor and are criticized for ideological bias (Source: Journal of Translation Studies, “Evaluating Mein Kampf Translations,” 2018).

For precise analysis, researchers should consult the 2016 critical edition or early German editions (Volksausgabe) and cross-reference with Manheim’s translation. This approach ensures fidelity to the original text and guards against revisionist distortions.

Conclusion: Truth Through Textual Evidence

The omitted passages on page 406 of James Murphy’s Mein Kampf translation highlight the complexities of translating a text as ideologically charged as Hitler’s manifesto. Their absence, likely due to an incomplete draft or Greta Lorke’s influence, underscores the need for careful textual comparison. National Socialist claims of Jewish influence in post-war translations like Manheim’s are largely unfounded, as evidenced by the 2016 critical edition and scholarly reviews. By grounding our understanding in the original German text and reputable sources, we can separate fact from propaganda and approach Mein Kampf with the critical rigor it demands.

For those studying Mein Kampf, I recommend starting with the Institute for Contemporary History’s critical edition and supplementing with Manheim’s translation. Avoid relying solely on Murphy’s version, and always verify key passages against the German original. In doing so, we honor the pursuit of truth over ideological narratives.

Sources

- Institute for Contemporary History. (2016). Hitler, Mein Kampf: Eine kritische Edition. Munich: Institut für Zeitgeschichte.

- The Guardian. (2016). “The Strange History of Mein Kampf in English.”

- Journal of Contemporary History. (1998). “The Red Orchestra and National Socialist Propaganda.”

- Translation Studies. (2005). “Ideology in Translation: Mein Kampf in English.”

- The National Archives. (2000). “National Socialist Records and the Fate of Hitler’s Manuscripts.”

- Publishers Weekly. (1995). “Translating Mein Kampf: A Historical Review.”

- Translation and Literature. (2007). “Bias in Manheim’s Mein Kampf.”

- Holocaust and Genocide Studies. (2003). “Mein Kampf in Post-War Translation.”

- Journal of Translation Studies. (2018). “Evaluating Mein Kampf Translations.”