Film/Television Review: Wit (2001)

There are films that, despite critical acclaim, should carry a disclaimer for viewers susceptible to depressive episodes. Wit, Mike Nichols’ 2001 made-for-television adaptation of Margaret Edson’s Pulitzer-winning play, is one such work. Its unrelenting focus on terminal illness, emotional isolation, and the dehumanising mechanics of modern medicine makes for an experience so oppressively bleak that it risks exacerbating mental anguish. While critics lauded its intellectual rigour and Emma Thompson’s committed performance, the film’s accolades feel undeserved—a case of artistic pretence masquerading as profundity. What could have been a poignant meditation on mortality instead becomes a gruelling slog through despair, its “wit” a thin veneer over a narrative steeped in nihilism. For those seeking catharsis or even basic human warmth, Wit is less a film than a punishment.

On paper, Wit boasts impeccable credentials. Adapted from Edson’s celebrated play by Nichols (an Oscar winner for The Graduate) and Thompson (a double Oscar recipient), it promised a searing exploration of life’s fragility through the lens of academia. Thompson stars as Dr. Vivian Bearing, a fiercely intellectual professor of 17th-century English poetry whose expertise in John Donne’s metaphysical sonnets frames her confrontation with metastatic ovarian cancer. Yet the film’s prestige trappings—its literary roots, A-list talent, and high-minded themes—cannot obscure its emotional sterility. What emerges is a project more invested in flaunting its intellectual bona fides than engaging the viewer’s humanity, a flaw that renders its suffering hollow and its insights shallow.

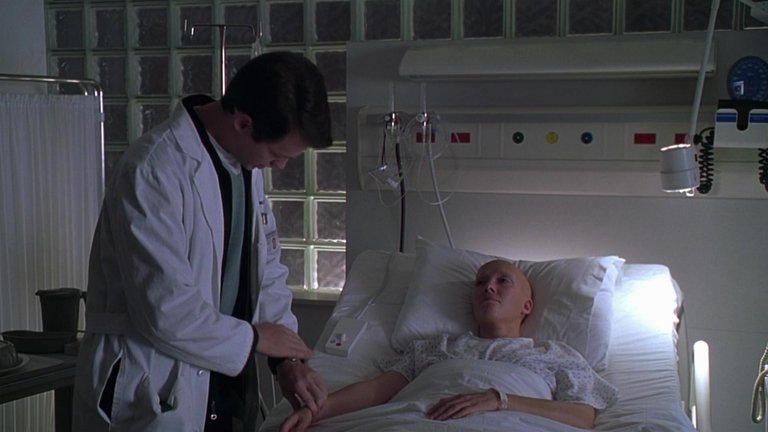

The plot follows Vivian’s diagnosis and subsequent enrolment in an aggressive chemotherapy trial overseen by Dr. Harvey Kelekian (Christopher Lloyd), a brusque oncologist who treats her as a research subject rather than a human being. Thompson’s performance is physically transformative—her shaved head, sunken cheeks, and trembling hands viscerally convey the toll of treatment—but the character’s emotional arc is stiflingly one-note. Vivian’s interactions with Dr. Jason Posner (Jonathan M. Woodward), a former student turned coldly ambitious physician, underscore her own complicity in prioritising intellect over empathy. Only nurse Susie Monahan (Audra McDonald) offers fleeting compassion, her kindness highlighting the systemic indifference of the medical establishment.

The film’s unflinching portrayal of Vivian’s degradation—vomiting, hair loss, invasive procedures—is undeniably brave, yet Nichols lingers on these moments with a voyeuristic detachment. The result is less a critique of medical dehumanisation than a fetishisation of suffering, turning Vivian’s body into a spectacle of decay. Her fourth-wall-breaking monologues, delivered with Thompson’s trademark wit, feel less like insights into her psyche than academic lectures, reinforcing her emotional isolation.

Premiering at the Berlin Film Festival before airing on HBO, Wit was positioned as a prestige television event. Nichols’ Emmy win for directing and the film’s Outstanding Made-for-Television Movie accolade cemented its reputation among critics, particularly those drawn to its highbrow sensibilities. Yet its small-screen origins betray its limitations. Confined to hospital rooms and lecture halls, the film feels claustrophobic, its stagebound aesthetic underscoring the material’s theatrical roots. Nichols’ direction, while competent, lacks cinematic inventiveness, relying on static shots and repetitive dialogue to propel the narrative. The decision to bypass cinemas speaks volumes: Wit is a film that demands admiration but resists connection, its appeal restricted to audiences who equate misery with depth.

Nichols, a master of adapting plays to screen, here struggles to transcend the source material’s limitations. The sparse settings—a sterile hospital, a university classroom—amplify Vivian’s isolation but also flatten the film’s visual language. Thompson’s performance, though technically impeccable, cannot compensate for the script’s reliance on monologues and didactic symbolism (e.g., Vivian’s hospital gown mirroring Donne’s “death’s head” imagery). The film’s few attempts at dynamism, such as flashbacks to Vivian’s teaching career, feel tacked on, serving as expositional crutches rather than emotional anchors.

Thompson’s physical commitment—shaving her head, adopting a gaunt demeanour—is laudable, yet the role demands more than mere endurance. Vivian’s intellectual arrogance, meant to humanise her, instead alienates; her journey from scholar to patient is less a reckoning with mortality than a clinical case study.

The film’s most glaring flaw is its refusal to grant Vivian meaningful human connections. Her lack of family, friends, or colleagues who genuinely care for her turns her plight into a solipsistic ordeal. Flashbacks reveal her as a merciless professor who belittled students and colleagues, framing her isolation as self-inflicted. Even Susie’s compassion feels transactional—a professional obligation rather than genuine kinship. This narrative choice, intended to critique Vivian’s emotional detachment, backfires: her suffering becomes a foregone conclusion, a karmic punishment for her intellectual pride.

The fourth-wall-breaking moments, where Vivian dissects her ordeal with academic precision, further distance the audience. Rather than inviting empathy, they reinforce her inability to engage authentically with others. The film’s bleakness is unrelenting, offering no redemption or growth—only the hollow satisfaction of seeing a “smug intellectual” humbled by death.

The film’s title promises sharp insight, but its “wit” amounts to little more than Vivian’s ability to quote John Donne’s Holy Sonnets while enduring chemotherapy. For viewers unfamiliar with Donne’s work—particularly his musings on death and salvation—these references are alienating, reducing profound poetry to academic showboating. The recurring refrain of “Death, be not proud” becomes a tiresome mantra, its theological complexity flattened into a trite slogan.

Worse, the film conflates erudition with emotional depth. Vivian’s intellectualism, far from illuminating her humanity, becomes a shield against vulnerability. Her final moments epitomise this failure: the poetry that defined her life offers no solace in death, rendering her journey a nihilistic punchline. The film’s insistence on privileging literary allusion over genuine feeling leaves viewers cold, its 98-minute runtime feeling like an eternity.

Wit is a film that mistakes bleakness for profundity and intellectual posturing for insight. Thompson’s performance, though brave, cannot salvage a script that reduces suffering to an academic exercise. Nichols’ direction, while polished, lacks the urgency or innovation needed to elevate the material beyond its stagebound origins. For all its accolades, Wit remains a punishing watch—a film that lectures its audience on mortality while offering none of the empathy that makes such meditations meaningful. Its greatest irony? In its quest to dissect the human condition, it forgets to be human.

RATING: 4/10 (+)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9