Film Review: Vice (2018)

In 2009, as he was leaving the White House, George W. Bush was probably the most hated man in the entire history of the United States up to that point. That’s why his claims that history would ensure this would not remain the case, and that future generations would view him and his presidency with far more understanding than his contemporaries, sounded laughable. Today, however, it no longer seems so ridiculous to recognise that Bush was right—not only does he no longer enjoy the status of the most hated man in history, but many intellectuals, politicians and celebrities who spent years building their reputations on opposing the 43rd U.S. president are now suddenly finding reasons to portray him as a likeable granddad, a great statesman and a misunderstood visionary.

This Gleichschaltung applies to Hollywood as well, although, due to the circumstances, films have been made whose content is still inadequately aligned with the new party directives. This is why Vice—which just a few years ago could have hoped for a heap of Oscars and critics’ panegyrics—had to settle for rather lukewarm praise from critics and the status of an outsider in awards season.

In a way, Vice isn’t so far from the new, revisionist stance on Bush’s presidency, given that it does not hold the likeable, well-intentioned, though essentially naive Dubya responsible for all the evil that occurred during his time, but rather a person who was much closer in character and other parameters to a typical Hollywood villain. Vice is short for Vice President, a role held for Bush’s eight years by Dick Cheney, who was convincingly the most hated among the wide array of Bush’s despised associates, because he was seen as a “grey eminence,” a personality pulling all the strings and making the most important decisions.

Cheney, unlike Bush, had no charisma and did not inspire particular sympathy, even among Bush’s supporters. He quickly became a sort of real-life equivalent of Darth Vader, a reputation he not only failed to oppose but could be said to have even enjoyed. It is therefore not hard to imagine that a film by Adam McKay—a writer and director who claimed before the premiere to hate the Bush administration from the depths of his soul—would pin the blame for all the misfortunes that befell America and the world in recent decades squarely on him, and that any attempt at an objective approach that tried to seriously explain or even justify Cheney’s actions would be ruled out from the start.

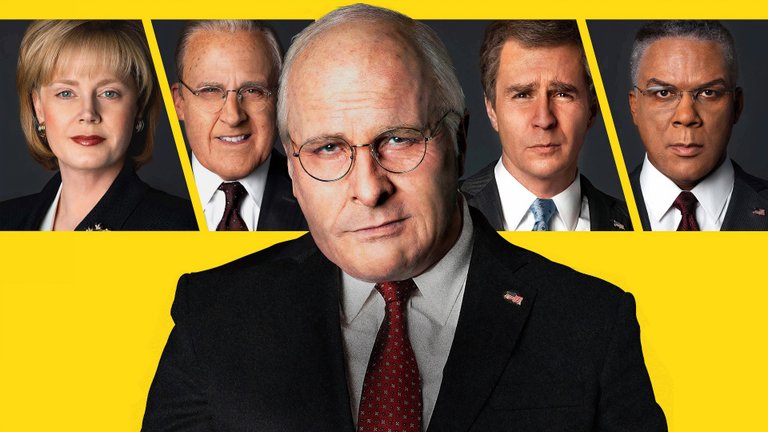

Vice uses a somewhat unconventional structure, mixing non-linear narration and the use of a fictional war veteran character, Kurt (Jessse Plemons), as a commentator with a more conventional portrayal of Cheney’s life and deeds. The film, in which Cheney is played by Christian Bale, thus begins in the 1960s in his native Wyoming, when the young Cheney is a deadbeat, kicked out of college and arrested for drunkenness and brawling. Fortunately for him—and unfortunately for the world—he has a girlfriend, Liz (Amy Adams), who forces him in time to sort his life out, finish his studies, start a family and seek a job in Washington.

There, he meets the colourful Republican congressman Donald Rumsfeld (Sreve Carell), who becomes his mentor and long-time collaborator, and through whom he gets a job in Nixon’s administration. It is there that he first encounters the methods by which the executive branch in a modern democracy can wage wars, make important decisions and practically govern the country and the rest of the world without being accountable to anyone.

After becoming White House Chief of Staff under President Ford, with Rumsfeld as Secretary of Defense, the two begin to build business and social ties with the business establishment, primarily oil corporations and the military-industrial complex, which for decades would torpedo environmental measures and social welfare spending. With their help, Cheney begins his own career as a congressman, continuing as Secretary of Defense under Bush Senior, and in 2000, without much trouble, accepts the offer from the inexperienced Bush Junior to be his vice-presidential candidate.

While American vice presidents were traditionally ceremonial figures, whose most important task was to wait for the president to die so they could replace him, Cheney had different ideas and would put them into action when he de facto seized power in the chaos after 11 September 2001. After that, it would not be too difficult for him to convince all the sceptics in the administration that Iraqi President Saddam Hussein possessed dangerous weapons of mass destruction and represented a threat that had to be removed by violently introducing democracy into Iraq.

Unlike the millions of Iraqis and several thousand American soldiers who would lose their lives because of this, or the several continents that would be devastated by wars and refugee crises, Cheney’s biggest problem at the time would be his own health, primarily a weak heart. McKay is an author who honed his craft working on comedies, and political engagement is not at all foreign to him, as evidenced most clearly by The Big Short, in which he portrayed the 2008 global financial collapse in a rather original and moving way.

Vice shares a similar approach with that film, mixing the righteous anger of a Hollywood leftist with black humour and stylistic experiments. However, the inevitable comparison between the two films is to the detriment of the latter, because instead of dealing with one global event, the film tackles a multi-decade political career and reduces it to a series of vignettes that attempt—not always in the most convincing way—to link Cheney to all the misfortunes that befell America and the world, from the Vietnam War all the way to Trump’s election as president.

Some of the experiments, which looked quite fresh in The Big Short, here seem like l’art pour l’art contrivances—examples include using the end credits sequence in the middle of the film, or the scene in which the Cheney couple recite Shakespeare’s Macbeth while making an important decision. This is not to say that the film lacks several moving scenes, but these are primarily thanks to the excellent cast.

This refers first and foremost to Christian Bale, who, striving to transform himself as best as possible into the former vice president, gained weight and created one of the most impressive characters in Hollywood films recently. Alongside him, Amy Adams as Liz Cheney and Carell as an equally striking Rumsfeld also did an excellent job, and Sam Rockwell is quite good in the relatively small and unimportant role of Bush.

The acting, as with many similar “Oscar-worthy” stalwarts, is Vice’s main trump card, and it could be said that Bale represents the best chance for McKay to go home singing after the awards ceremony. On the other hand, regardless of how that turns out, this film will leave a bitter taste in the mouth of most viewers—not only because of the subject matter it deals with, but also because of the realisation that, as in many similar cases, the opportunity for a truly great achievement was missed.

RATING: 5/10 (++)

(Note: The text in the original Croatian version is available here.)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

LeoDex: https://leodex.io/?ref=drax

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9