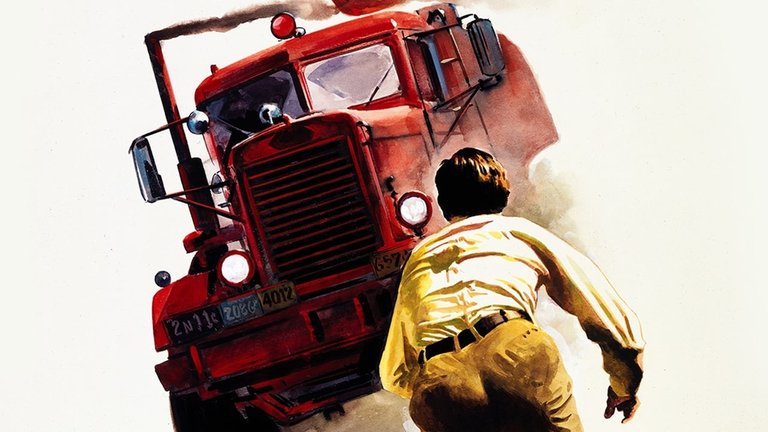

Film Review: Duel (1971)

For decades, television was widely regarded as the inferior sibling of cinema, constrained by technological limitations, modest budgets, and a reliance on serialized storytelling that diluted the grandeur of cinematic spectacle. The medium’s perceived inadequacy in delivering the visceral thrills and visual splendour of the silver screen made it a secondary platform for artistic ambition. It took a rare confluence of vision and skill to challenge this hierarchy, and few filmmakers have achieved such a feat as Steven Spielberg with his 1971 television film Duel. This taut, nerve-shredding thriller not only marked Spielberg’s emergence as a cinematic prodigy but also shattered the artificial boundaries between television and cinema. By transforming a modestly budgeted TV project into a gripping, atmospheric feat of suspense, Duel became a landmark in both Spielberg’s career and the evolution of the medium itself, proving that television could rival the big screen in narrative power and technical ingenuity.

The film’s origins lie in the speculative fiction of Richard Matheson, a titan of 20th-century horror and science fiction whose works, including I Am Legend and What Dreams May Come, blended psychological depth with speculative premises. Matheson’s short story Duel, published in Playboy in March 1971, drew from a real-life encounter he had in 1963 while driving in California, where a truck driver’s erratic tailgating left him unnerved. This visceral experience became the seed for a tale of paranoia and existential dread, which Matheson had long sought to adapt into a film. Universal Television’s acquisition of the rights brought the story to Spielberg, then a 26-year-old director with only a handful of TV episodes under his belt. The film aired as part of ABC’s Movie of the Week series on 13 November 1971, captivating audiences and critics alike with its relentless pacing and claustrophobic tension. Its success prompted Universal to fund additional scenes, enabling a theatrical release in 1972. This dual platform triumph catapulted Spielberg into Hollywood’s spotlight, cementing his reputation as a visionary storyteller capable of transcending medium-specific limitations.

At its core, Duel is a study of isolation and survival. Dennis Weaver’s David Mann, a middle-aged salesman traversing the barren highways of the Mojave Desert, embodies the Everyman thrust into extraordinary peril. Mann’s mundane existence—defined by corporate drudgery and a strained marital relationship, hinted at through a terse phone call with his wife (played by Jacqueline Scott)—contrasts starkly with the escalating chaos that ensues when a grotesque, rusted tanker truck begins stalking him. Spielberg frames the truck as both a physical antagonist and a manifestation of Mann’s inner anxieties: a symbol of entrapment and existential insignificance. The cat-and-mouse game between Mann and the anonymous truck driver escalates from tense near-misses to outright violence, with Mann’s attempts to seek refuge in roadside diners and gas stations proving futile. Each encounter deepens the stakes, culminating in a climax where the desert highway becomes a lethal arena, and Mann’s survival hinges on wits and sheer desperation.

While Spielberg’s Los Angeles 2017 is technically his first feature-length directorial effort, Duel is universally acknowledged as his true debut. This distinction arises not merely from its theatrical release but from its thematic and stylistic maturity. Los Angeles 2017, part of The Name of the Game series, was a speculative thriller exploring dystopian themes, but its fragmented structure and modest ambition paled in comparison to the tight focus and technical precision of Duel. The latter’s singular narrative, self-contained world, and singular protagonist allowed Spielberg to demonstrate his ability to craft a cohesive, emotionally resonant story within the constraints of television. By the time of Duel, Spielberg had honed his craft through years of TV work, and the film’s success marked a turning point in his career, paving the way for projects like Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Spielberg’s debt to Alfred Hitchcock is palpable in Duel, particularly in its meticulous construction of suspense. Like Hitchcock’s classics, the film thrives on the gradual escalation of tension, with the threat of violence lingering just beyond the frame until the moment of explosive payoff. Spielberg’s camera work—whether lingering on the truck’s imposing silhouette, the claustrophobic interior of Mann’s car, or the vast, empty desert—creates a suffocating atmosphere of dread. The director’s ability to milk suspense from minimal dialogue and plot complexity is masterful; the truck, never fully seen or personified, becomes a bogeyman of modernity, embodying the faceless menace of an uncaring world. Critics and scholars have long hailed Duel as a textbook example of how to craft suspense within budgetary and logistical constraints, a testament to Spielberg’s intuitive grasp of pacing and visual storytelling.

Central to the film’s appeal is its adherence to Hitchcock’s principle of placing an ordinary individual in extraordinary peril. Mann is no action hero; he is a weary, unremarkable man whose only weapon is his wits. Weaver’s performance—subtle, understated, and filled with mounting desperation—anchors the film’s psychological depth. Mann’s initial attempts to rationalize the truck driver’s actions (“Maybe he’s just in a hurry,” he mutters) underscore his denial of the escalating threat, while his later breakdowns reveal a man stripped of all societal pretence, reduced to primal survival instincts. The film’s critique of corporate alienation and suburban conformity is subtle but present: Mann’s job as a salesman reflects a life of hollow routine, and the open road, which initially offers him an illusion of freedom, becomes a prison of fear.

Spielberg amplifies the film’s terror by keeping the truck driver shrouded in mystery. Only a hand and a shadowy figure emerge from the cab, leaving the audience—and Mann—to speculate about his motives. Is the driver a psychopath, a demon, or merely a product of the desert’s harsh, indifferent environment? The ambiguity ensures that the threat feels universal and archetypal, transcending the specifics of the plot. This technique, akin to the unseen shark in Jaws, forces the audience to project their own fears onto the antagonist, making the suspense visceral and personal. The truck itself becomes a character, its rusted exterior and lumbering movements evoking a monstrous, unstoppable force.

Despite its brilliance, Duel is not without its minor flaws. The film’s opening stretches slightly, with Mann’s mundane drive and interactions feeling padded to meet the 90-minute runtime. Additionally, the motivations of the truck driver remain frustratingly vague, a choice that heightens suspense but leaves some viewers unsatisfied. These minor missteps, however, are emblematic of Spielberg’s relative inexperience at the time and are easily overshadowed by the film’s relentless momentum and technical assuredness.

Duel’s impact on Spielberg’s career cannot be overstated. Its themes of survival against an implacable foe, its use of the environment as a character, and its mastery of suspense directly informed Jaws (1975), cementing Spielberg’s reputation as a maestro of the thriller. Beyond Spielberg’s work, the film’s desert highway setting inspired a host of very different films, including Roadgames (1981), Mad Max: The Road Warrior (1981), and The Hitcher (1986). The motif of the isolated highway as a battleground persists in modern media, a testament to Duel’s enduring influence on the genre.

While Duel remains a compelling watch, its premise occasionally feels anachronistic in the age of smartphones and dashcams. Today’s audiences, accustomed to instant communication and constant connectivity, may question why Mann cannot simply call for help or document the truck’s license plate. Similarly, the lack of modern safety features in his car—such as airbags or GPS—heightens the peril but strains plausibility. These elements, while forgivable in 1971, now contribute to a sense of quaintness, a challenge shared with later films like Joy Ride (2001). Yet, the film’s core tension—human fragility against an indifferent universe—retains its emotional resonance, ensuring its place in the canon of suspense cinema.

For all its modest origins and occasional datedness, Duel stands as a remarkable achievement, a testament to Spielberg’s innate talent and his ability to elevate low-budget constraints into artistic strengths. It is a film that thrives on atmosphere, character, and the relentless pacing of its director’s imagination. While its legacy has been overshadowed by Spielberg’s later blockbusters, Duel remains a vital entry in his filmography, a proof of concept for the themes and techniques that would define his career. To dismiss it as merely a “television movie” is to overlook its ambition and innovation. For audiences seeking a masterclass in suspense, Duel rewards with its blend of psychological depth and visceral thrills—a reminder that even on the smallest screen, a visionary filmmaker can conjure cinematic magic.

RATING: 8/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9