Film Review: Deliverance (1972)

Deliverance (1972), directed by John Boorman and based on James Dickey’s 1970 novel, remains a landmark in American cinema for its unflinching exploration of the deep-seated urban-rural divide. This rift, one of the oldest and most enduring fissures in American society, has long been a source of fascination—and exploitation—for Hollywood. Few films have capitalised on this tension as effectively as Deliverance, which not only delivers a taut, visceral adventure story but also reinforces cultural stereotypes that have since permeated global imagination. The phrase “Deliverance country” has since entered colloquial lexicon as shorthand for remote, inhospitable regions where civilisation’s boundaries fray, and where danger lurks in every shadow. The film’s success lay in its ability to blend thrills with social commentary, yet its legacy is equally tied to the uncomfortable stereotypes it perpetuated about rural America, stereotypes that continue to resonate in popular culture decades later.

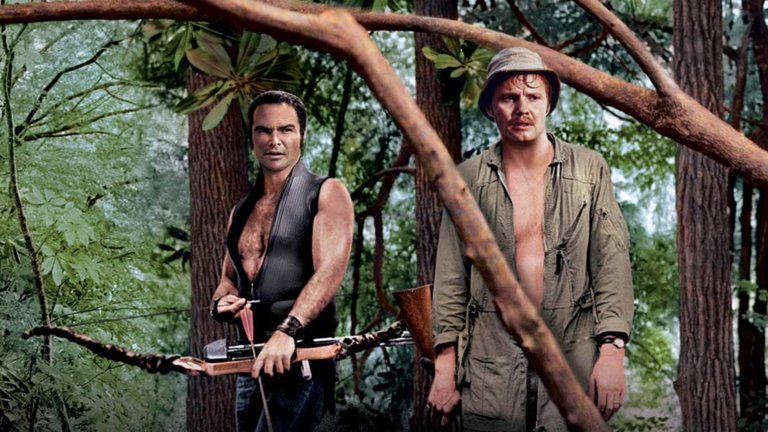

The story’s roots in Dickey’s novel are crucial to understanding its complexity. As both author and screenwriter, Dickey brought a nuanced perspective to the narrative, having grown up in Georgia, the film’s setting. His dual role as creator and participant—he also appears briefly as a sheriff—imbued the project with a personal stake, though this did not prevent clashes with Boorman during production. The film’s protagonists are four Atlanta businessmen: Ed Gentry (Jon Voight), Lewis Medlock (Burt Reynolds), Bobby Trippe (Ned Beatty), and Drew Ballinger (Ronny Cox), who embark on a canoe trip down the Cahulawassee River in northeastern Georgia. Their journey is framed as a quest for adventure, but it is also a last chance to experience the river before it is flooded by a hydroelectric dam, a development that threatens to erase both the landscape and the rural communities clinging to it. This environmental subplot, often overshadowed by the film’s horror elements, adds depth to what might otherwise be a straightforward survival tale.

The plot’s progression is marked by escalating tension, beginning with the men’s uneasy interactions with locals. The hostility they encounter hints at the underlying conflict between urban progress and rural resistance. When Bobby and Ed stumble upon a pair of mountain men—played by Billy McKinney and Herbert Coward—their capture and subsequent trauma elevate the stakes. The rape of Bobby and the violent confrontation that follows—a scene where Lewis kills one captor with an arrow—cement the film’s exploration of primal fear. Yet the true horror unfolds not merely in these moments of violence but in the moral ambiguity that follows. Lewis insists on burying the body and concealing the incident, a decision that haunts the group as they navigate treacherous rapids and face the possibility of being hunted. The film’s climax, marked by Drew’s death and Lewis’s injury, leaves the survivors grappling with survival and guilt, their journey from civilisation to wilderness mirroring a descent into existential uncertainty.

On a superficial level, Deliverance leans into Hollywood’s tendency to portray rural Americans as primitive, ignorant, and dangerous. The “crackers” of the film’s backwoods are depicted as genetically degenerate, their isolation breeding incest and a brutality that erupts without warning. The infamous “Dueling Banjos” scene—where Drew’s folk music is outdone by a local boy’s virtuosic playing—initially suggests a bridge between cultures, but the scene’s ominous undertones at the very end foreshadow the violence to come. This duality—beauty and danger, connection and division—is central to the film’s power, yet it also underscores its participation in reinforcing harmful stereotypes. The mountain men are reduced to caricatures of savagery, their humanity stripped away in service of the urban protagonists’ ordeal.

However, Dickey’s authorship adds layers that resist simplistic categorisation. The environmental angle, though underemphasised in many analyses, is a key thread. The dam project symbolises the encroachment of modernity on rural life, a loss felt acutely by the locals. The haunting sequence where they exhume graves to relocate them before the flood—a ritual of displacement—elevates the film into a meditation on cultural erasure. Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond’s lush, chiaroscuro visuals juxtapose the river’s beauty with its lethality, suggesting that nature itself is an antagonist. The rapids, which claim Drew’s life, are as merciless as any human foe, reminding viewers that the wilderness is indifferent to civilisation’s boundaries.

The film’s true brilliance lies in its subversion of character expectations. Lewis, the confident outdoorsman, is revealed as morally compromised, prioritising expediency over honesty. Drew, the most empathetic and principled of the group, dies tragically, his idealism undone by circumstances. Bobby, the physically vulnerable member, survives unscathed, while Ed, initially the most passive of all, must confront his own cowardice to secure their survival. This inversion of archetypes—particularly Reynolds’s performance, which balances charisma with moral ambiguity—prevents the film from descending into a mere survival saga. Instead, it becomes a study of masculinity, responsibility, and the fragility of civilised pretence.

Production challenges mirrored the film’s themes of conflict and survival. Shot on location in Georgia’s real Cahulawassee River (a decision that later drew criticism for environmentalists), the film’s low budget forced actors to perform their own stunts, leading to injuries and near-misses. Tensions between Dickey and Boorman—whose “arthouse” sensibilities clashed with the project’s need for mainstream appeal—nearly derailed the production. Yet these struggles contributed to the film’s raw authenticity. Boorman’s decision to adopt a conventional narrative structure, blending adventure, horror, and social critique, created a unique hybrid that defied easy categorisation. The result is a film that thrills while provoking reflection, a rare feat in 1970s cinema.

The film’s only significant misstep lies in its closing sequence. The infamous scene of a decomposing hand emerging from the dam’s waters—a reveal as a nightmare—has since been parodied and imitated in countless horror films, from Carrie to Friday the 13th. While effective in its ambiguity, the sequence risks diluting the film’s earlier gravitas by leaning into exploitation tropes.

Deliverance is as a flawed masterpiece. Its exploitation of rural stereotypes, though problematic, is counterbalanced by its layered exploration of environmental loss, moral ambiguity, and the fragility of civilisation. Dickey and Boorman’s collaboration, despite its on-set tumult, produced a film that transcends its genre boundaries, offering a bleak yet compelling vision of America’s divides. While its legacy includes perpetuating harmful myths about rural life, its unflinching storytelling and technical brilliance cement its place as a cornerstone of 1970s cinema—a film that continues to unsettle and provoke long after its final frame.

RATING: 8/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Posted Using INLEO

Never heard of this one but it seems to be getting a good score. I bookmarked it on my backlog watchlist.