Film Review: Blow-Up (1966)

In the annals of cinema, it is not uncommon to encounter films that swiftly ascend to the pantheon of cultural significance, often hailed as landmarks of innovation or social commentary. Yet, some of these works endure not for the reasons their creators or early champions originally proposed, but because they evolve into vessels for new interpretations as time shifts societal priorities. Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, a 1966 mystery drama set in London’s mod underworld, epitomises this phenomenon. While it remains a touchstone of 1960s cinema, its status as a “classic” is contentious. Critics, film scholars, and nostalgic Boomers may revere it as a definitive work of existential cinema, but Blow-Up resists easy categorisation. Its legacy is less about grand artistic statements and more about its paradoxical duality: a film that simultaneously embodied the era’s rebellious spirit and foreshadowed the collapse of traditional cinematic norms.

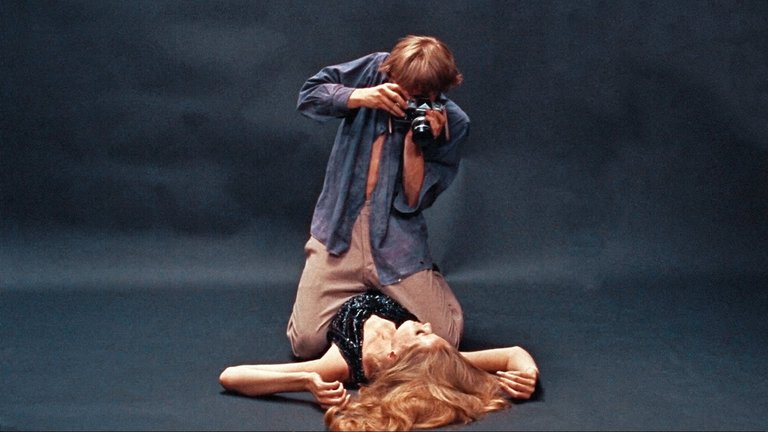

Adapted from Julio Cortázar’s short story “Las babas del diablo” (”The Devil’s Drool”), Blow-Up follows Thomas (David Hemmings), a self-absorbed fashion photographer whose life oscillates between decadence and existential drift. His London studio thrives on the allure of supermodels like Veruschka, who parade through his frames or proposition sex in exchange for fame. One afternoon, Thomas wanders into a park, where he snaps photos of what appears to be a woman (Vanessa Redgrave) and an older man (Ronan O’Casey) engaged in a clandestine affair. The woman, later identified as Jane, demands the negatives, even offering herself sexually. Intrigued, Thomas develops the film and discovers what might be a murder: a man’s body lies motionless, though the evidence remains ambiguous. His subsequent search for clarity—zooming in on grainy negatives, stumbling upon the corpse, and confronting a ransacked studio—culminates in a surreal tennis match with mimes, leaving the mystery unresolved. Antonioni’s refusal to clarify the central question—was it a murder or a hallucination?—anchors the film in the subjective, blurring reality and perception.

Produced by Carlo Ponti and distributed by MGM, Blow-Up marked Antonioni’s first English-language film, a departure from his earlier Italian arthouse triumphs like L’avventura (1960) and La notte (1961). Those films probed the alienation of modernity through glacial pacing and existential angst, themes that permeate Blow-Up but are refracted through a more accessible lens. Thomas embodies the director’s signature antihero: a man of privilege yet profound disconnection, whose hedonism masks a void. The unresolved mystery mirrors L’avventura’s famous plot abandonment, but here, Antonioni infuses the narrative with pop culture trappings—swinging London’s fashion, jazz, and rock ’n’ roll—to appeal to mainstream audiences. This hybridity made Blow-Up both a critical darling and a box-office success, bridging high art and mass entertainment.

The film’s immediate cultural impact lay in its audacity. Antonioni, exploiting 1960s liberalism, saturated Blow-Up with material that would have been unthinkable under Hollywood’s Production Code: explicit sex, drug use, and nudity. MGM, capitalising on urban art-house markets, bypassed certification, gambling that the film’s avant-garde reputation would shield it from backlash. This gambit succeeded, accelerating the Code’s demise and paving the way for the MPAA’s ratings system in 1968. Yet, the “shock value” that once made Blow-Up controversial now seems quaint. Its true lasting significance lies elsewhere.

Today, Blow-Up endures not for its plot but as a visual and auditory document of 1960s counterculture. The film’s London—a labyrinth of mod fashion, Carnaby Street boutiques, and psychedelic hairstyles—is a meticulously crafted artifact. Thomas’s studio, a nexus of aspiring models and hip photographers, mirrors the era’s obsession with youth and transience. The soundtrack, blending Herbie Hancock’s jazz and the Yardbirds’ raucous rock, amplifies the sensory overload. The climactic rock concert, where Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck perform as themselves, crystallises the film’s immersion in the zeitgeist. For modern viewers, this is the film’s greatest charm: a window into a world where rebellion was still novel enough to feel dangerous.

The ensemble cast embodies the film’s dual identity. David Hemmings, inspired by the androgynous cool of photographer David Bailey, delivers a performance of detached intensity. His Thomas is a man who thrives only when behind the camera, his curiosity and restlessness animating the plot. Vanessa Redgrave’s Jane—a femme fatale whose motives remain shadowy—adds mystery, while Jane Birkin’s debut as a model auditioning for Thomas underscores the transactional nature of fame. Veruschka’s cameo as herself, draped in avant-garde attire, epitomises the fashion scene Antonioni immortalises. Yet, the film’s greatest “actor” is London itself, rendered as a character of neon-lit streets and hidden secrets.

Antonioni’s longtime collaborator, cinematographer Carlo Di Palma, elevates the film’s visual poetry. The park sequence, with its shifting perspectives and blurred focus, mirrors Thomas’s quest for clarity. The studio’s stark interiors, bathed in harsh light, contrast with the park’s dappled shadows, symbolising the tension between artifice and reality. Di Palma’s use of close-ups on Thomas’s enlargements—a literal magnification of the film’s themes—transforms photography into a metaphor for cinema itself: a medium that claims to capture truth yet often distorts it.

The film’s script, co-written by Antonioni and Tonino Guerra, occasionally falters. Subplots, such as Thomas’s affair with Patricia (Sarah Miles), a woman shared with his friend, feel tacked-on, their relevance to the central mystery unclear. The climactic mime sequence, while thematically resonant, descends into self-indulgent abstraction, alienating viewers expecting closure. These missteps highlight Antonioni’s prioritisation of mood over narrative cohesion—a hallmark of his style but one that risks leaving audiences adrift.

Blow-Up’s ambiguity lent itself to reinterpretation. Decades after its release, critics drew parallels between Thomas’s photographs and Abraham Zapruder’s footage of JFK’s assassination, both documents of violence that outstrip their creators’ control. Thomas’s futile search for truth—zooming in on negatives only to find indistinct pixels—prefigures the paranoid thrillers of the 1970s, such as The Parallax View. His inability to discern reality from illusion critiques not just individual obsession but the era’s broader disillusionment with institutions.

The film’s DNA persists in later works. Mel Brooks’ High Anxiety (1977) parodies Antonioni’s style, transplanting Blow-Up’s existential dread into a Hitchcockian thriller. Brian De Palma’s Blow Out (1981) directly borrows the premise of a photographer (replaced by a sound engineer) inadvertently capturing a political assassination. Both films acknowledge Blow-Up’s blueprint for blending mystery with philosophical inquiry, ensuring its influence outlives its plot’s dated elements.

Blow-Up resists the label of “classic,” preferring instead to linger in the liminal space between art and exploitation, clarity and obscurity. Its significance lies not in its resolution—or lack thereof—but in its role as a cultural artifact. It is a film that captured the 1960s’ contradictions: a decade of liberation and paranoia, where rebellion against norms led to new forms of alienation. Antonioni’s refusal to simplify his vision, even as he courted mainstream audiences, ensures Blow-Up remains a challenge to reductive analysis. To dismiss it as merely a product of its time overlooks its enduring questions about perception, truth, and the artist’s role in an indifferent world. In this sense, Blow-Up is not a relic but a mirror, reflecting each new generation’s anxieties back at itself.

RATING: 7/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9

Congratulations @drax! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 570000 upvotes.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP