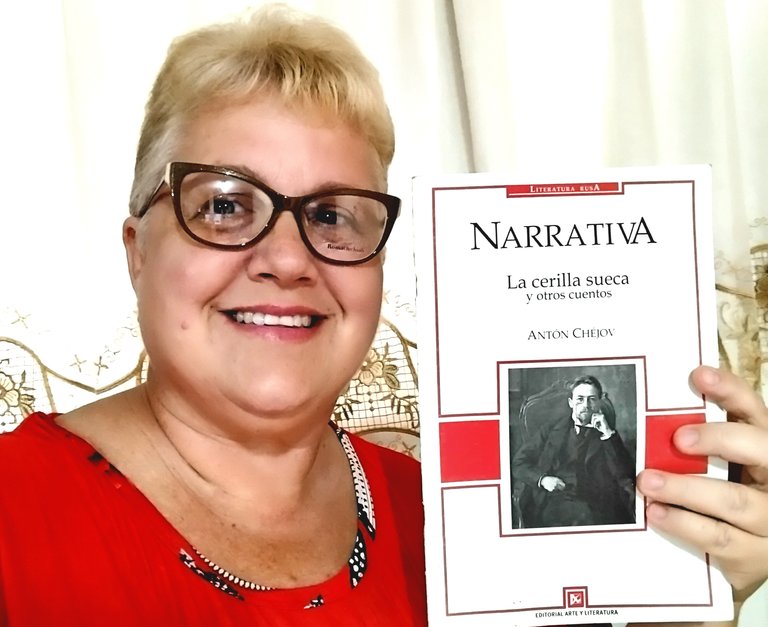

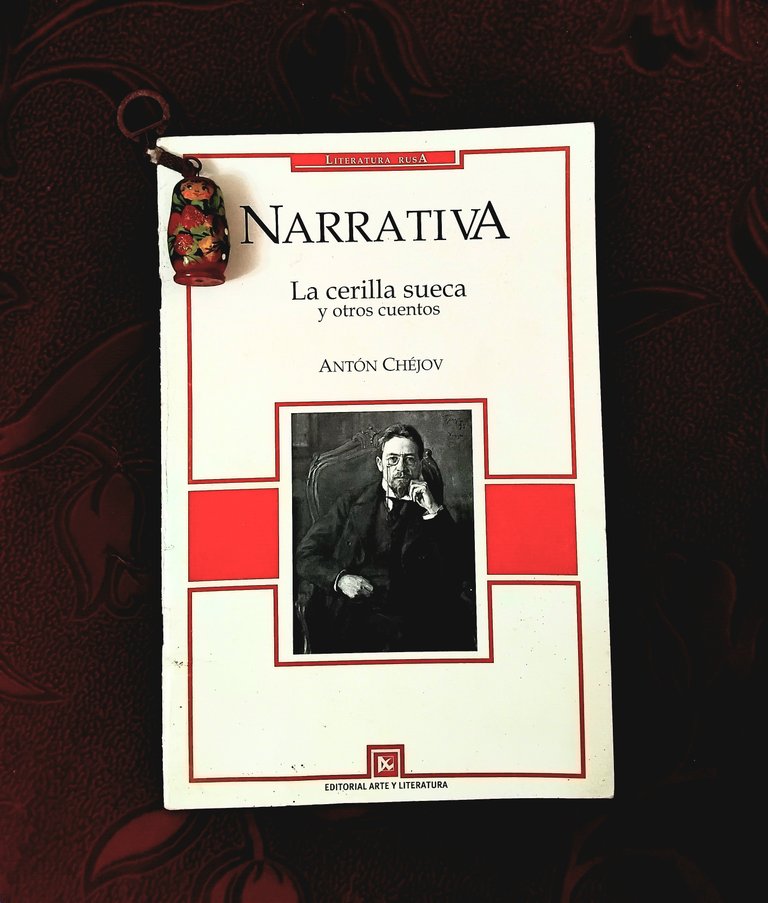

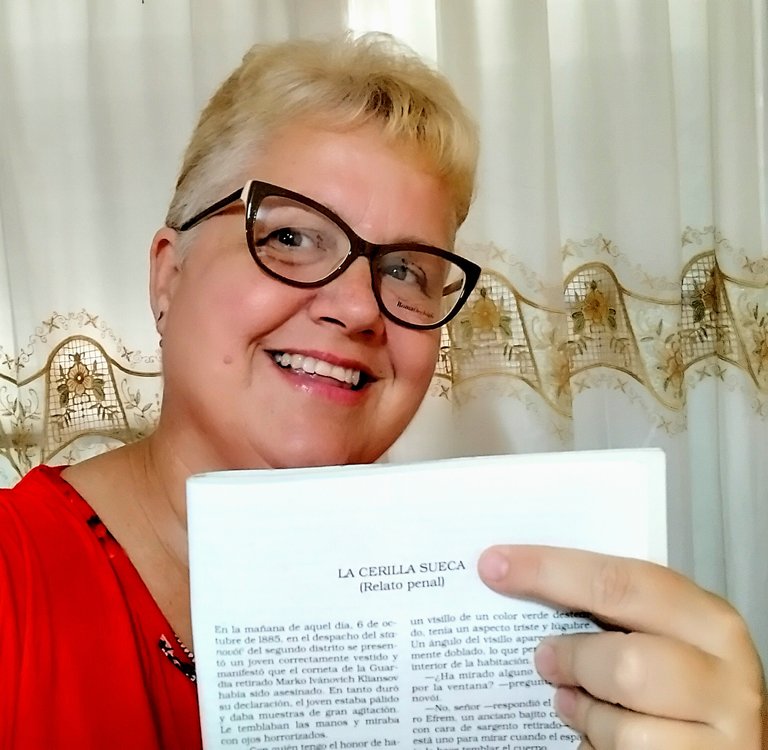

The Swedish Match by Antón Chéjov || Review 《🔥》La cerilla sueca de Antón Chéjov || Reseña.

I've always been fond of Anton Chekhov's style. To me, he is undoubtedly a master of the short story, and I feel his way of writing attracts me in a strange and special way. His genius lies not only in his capacity to show the pathetic side of human beings or their psychological depth, but also in that fine and devastating irony that seems to whisper the truth in your ear with a smile.

"The Swedish Match" is precisely one of those stories I love to reread. It is a brilliant parody of the detective genre, a masterclass in how to tell a story with just the essentials, and such an accurate satire on our human nature. With apparent simplicity, Chekhov shows us how we prefer to invent complex dramas rather than accept a simple and mundane truth. Through the trivial investigation of a disappearance, he deploys his entire arsenal: the detail that reveals everything, an objectivity that stings, humor as criticism, and a deep understanding of his characters' psychology that makes them tremendously real.

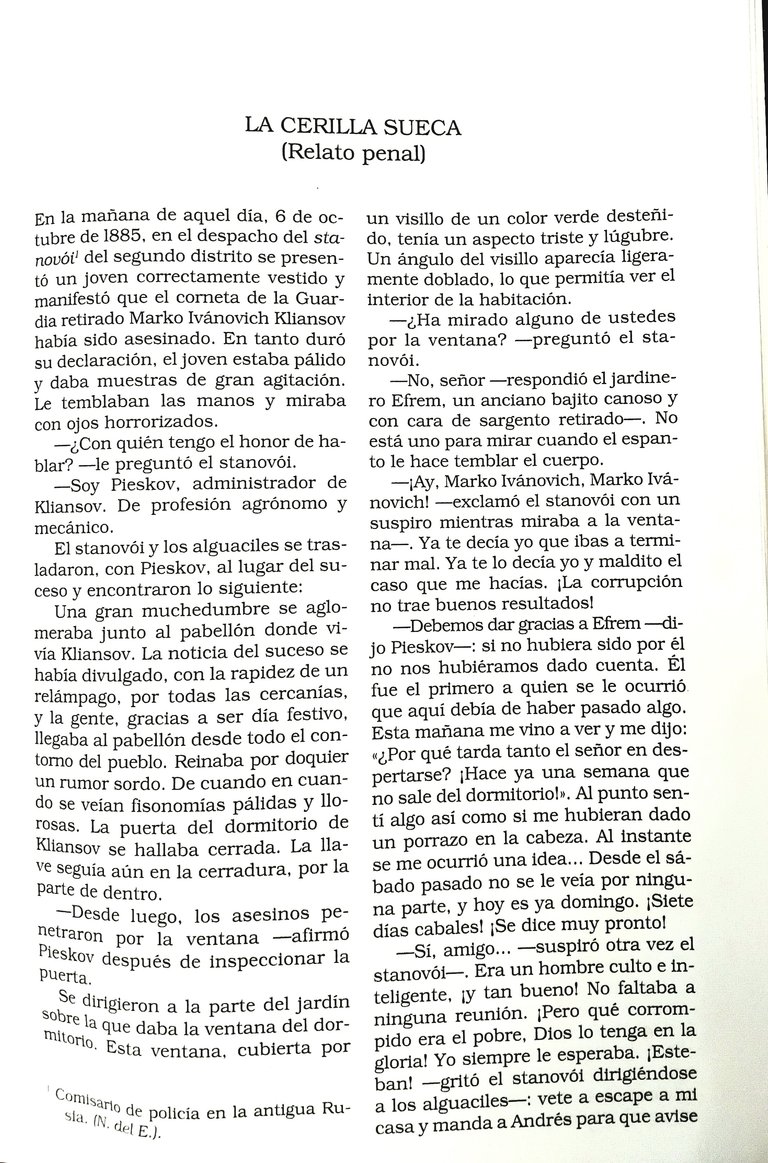

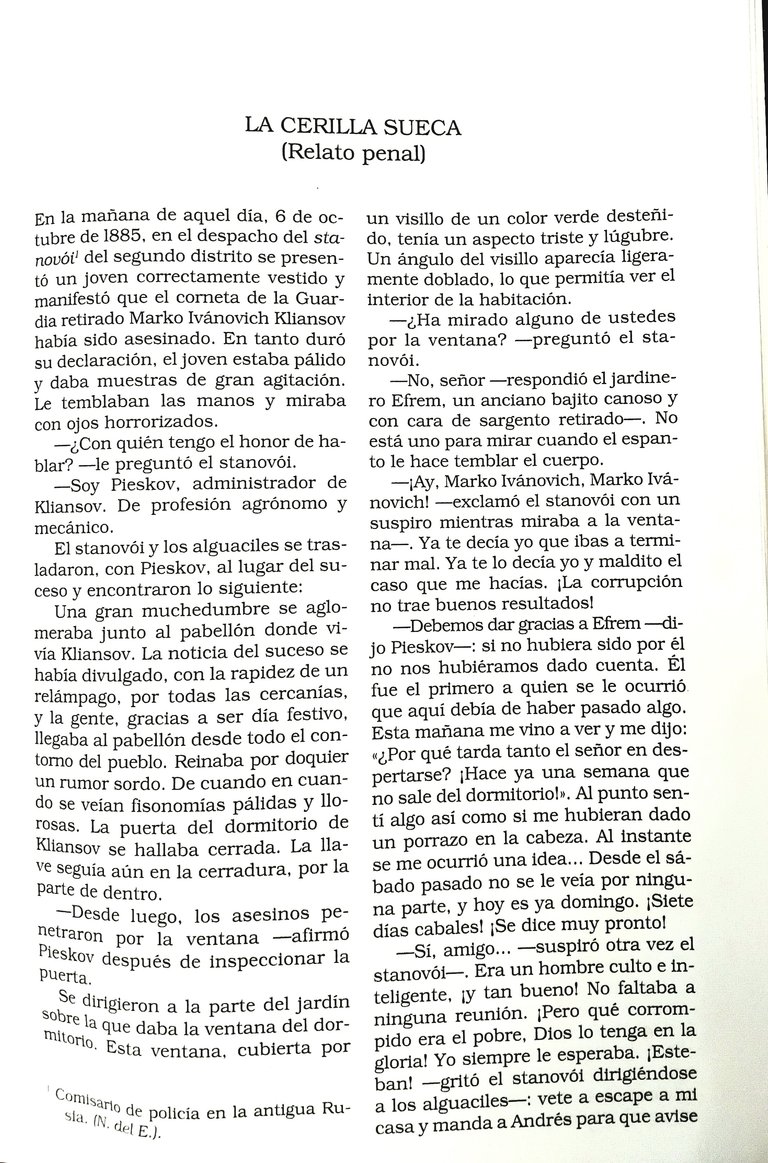

The plot begins with a classic mystery: the landowner Marko Ivanovich Klyauzov has disappeared. His room is a chaos that screams "crime" from all corners: overturned furniture, money scattered on the floor, and most chillingly, bloodstains on the pillow. The authorities who arrive at the scene are a pair of characters that Chekhov paints with perfect strokes. There is the investigating magistrate Nikolai Yermolaich, a man more interested in his own comfort than in solving the case, and the police superintendent Dukovski, young, enthusiastic, and immediately enamored with the idea of a perfect murder. Dukovski is that type of person we've all encountered at some point. He represents the intellectual arrogance of someone who wants to see mystery where there is none. He has already convinced himself that the estate manager, Evgraf Kuzmich, is the murderer, and from there, everything forcibly fits into his theory. They interrogate servants, follow false leads, and search for a corpse that never appears, entangling themselves more and more in a web of their own invention.

And this is where Chekhov applies, with a mastery that fascinates me, his principle of objectivity and narrative economy. The narrator remains distant, almost journalistic, describing actions and dialogues without entering into judgments or lengthy internal monologues. He doesn't tell us "look how stupid they are"; he shows us the stupidity in action, and this narrative coldness makes the comic effect even more brilliant. As a reader, you sense, just like the magistrate, that something doesn't add up in Dukovski's speculations, but Chekhov forces you to be a witness to the farce, trusting that reality will eventually impose itself.

The resolution of the story is simply a stroke of genius. It is the ultimate expression of the significant detail, that very Chekhovian concept. He himself said that if a rifle is hanging on the wall in the first act, it must be fired in the second or third. Well, here he inverts the principle: the gun everyone thinks they see (the murder) never existed, and it is a tiny and irrelevant object that triggers the outcome. Tired and wanting to smoke, Magistrate Yermolaich looks for a match. Not finding one, he glances almost by chance inside a bedside lamp in the room... and there he is. Not a corpse, but Marko Ivanovich himself, hidden, fast asleep, and dead drunk.

The "Swedish match" thus becomes that trivial detail that demolishes an entire dramatic architecture built on vanity and incompetence. The explanation is ridiculously simple: Klyauzov, in a state of epic drunkenness, started a fight, threw everything, cut himself accidentally, and, to continue sleeping without being disturbed, took refuge in the only place he could think of: the bedside lamp. The entire investigation, with its suspicions and accusations, was an absurd exercise in self-deception.

This ending allows Chekhov to exercise a deeply humorous social and psychological criticism. He affectionately mocks the pomposity of authority, those characters who prefer a thousand elaborate theories over admitting the evidence of human simplicity. Dukovski isn't seeking the truth; he's seeking an exciting story that confirms his own intelligence. Chekhov shows us how boredom and vanity are often the engine of our greatest foolishness. And in the end, the story reflects that benevolent pessimism he held towards the human condition: our most dramatic outbursts often have banal and pathetic roots, like drunkenness or laziness.

"The Swedish Match" is, ultimately, a masterful work that condenses all of Chekhov's narrative art. Through parody, economy of resources, the revealing detail, and an objectivity that hurts more than any judgment, the author reveals a universal truth to us: humanity often errs not out of malice, but out of a blind arrogance that prevents it from seeing what is right under its nose. The truth, Chekhov tells us, is not always hidden in the shadows; sometimes, it is hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone, out of pure everyday need like lighting a cigarette, to find it.

I am a Doctor of Microbiology, a lover of nature, literature, music, cooking, and life itself. A staunch defender of family and children.

The texts are written by me without the use of AI.

Banners created on Adobe Fireworks courtesy of @azufrecs

Thank you for visiting my blog.

The photos are my property

ESPAÑOL

Siempre me ha gustado el estilo de Antón Chéjov. Para mí, es sin duda un maestro del relato corto, y siento que su forma de escribir me atrae de una manera extraña y especial. Su genialidad no reside solo en esa capacidad para mostrar lo patético del ser humano o su profundidad psicológica, sino también en esa ironía fina y demoledora que parece susurrarte la verdad al oído con una sonrisa.

"La cerilla sueca" es, justamente, uno de esos cuentos que me encanta releer. Es una parodia brillante del género policial, una lección magistral de cómo contar una historia con lo justo, y una sátira tan certera sobre nuestra naturaleza humana. Chéjov nos muestra, con aparente simpleza, cómo preferimos inventar dramas complejos antes que aceptar una verdad simple y mundana. A través de la investigación trivial de una desaparición, despliega todo su arsenal, el detalle que lo revela todo, una objetividad que duele, el humor como crítica y una comprensión profunda de la psicología de sus personajes que los hace tremendamente reales.

La trama arranca con un misterio clásico, el terrateniente Marko Ivánovich Klyauzov ha desaparecido. Su habitación es un caos que grita "crimen" por los cuatro costados hay muebles volcados, dinero esparcido por el suelo y lo más escalofriante, manchas de sangre en la almohada. Las autoridades que llegan al lugar son un par de personajes que Chéjov pinta con trazos perfectos. Está el juez de instrucción Nikolai Yermoláich, un hombre más interesado en su propia comodidad que en resolver el caso, y el comisario Dukovski, joven, entusiasta y inmediatamente embelesado con la idea de un asesinato perfecto. Dukovski es ese tipo de persona que todos hemos conocido alguna vez. Representa la soberbia intelectual de quien quiere ver misterio donde no lo hay. Él ya se ha convencido de que el administrador, Evgraf Kuzmich, es el asesino, y a partir de ahí, todo encaja forzadamente en su teoría. Interrogan a sirvientes, siguen pistas falsas y buscan un cadáver que no aparece, enredándose cada vez más en una madeja de su propia invención.

Y aquí es donde Chéjov aplica con una maestría que me fascina su principio de objetividad y economía narrativa. El narrador se mantiene distante, casi periodístico, describiendo acciones y diálogos sin entrar en juicios ni monólogos internos larguísimos. No nos dice "miren qué estúpidos"; nos muestra la estupidez en acción, y esa frialdad narrativa hace que el efecto cómico sea aún más brillante. Como lector, intuyes, igual que el juez, que algo no cuadra en las elucubraciones de Dukovski, pero Chéjov te obliga a ser testigo de la farsa, confiando en que la realidad, tarde o temprano, se impondrá por sí sola.

La resolución del cuento es simplemente un golpe de genialidad. Es la máxima expresión del detalle significativo, ese concepto tan chejoviano. Él mismo decía que si en el primer acto hay una escopeta colgada, en el segundo o tercero debe dispararse. Pues aquí invierte el principio: la pistola que todos creen ver (eal asesinato) nunca existió, y es un objeto ínfimo e irrelevante el que provoca el desenlace. Cansado y con ganas de fumar, el juez Yermoláich busca una cerilla. Al no encontrar, mira casi por azar dentro de un velador en la habitación... y ahí está. No un cadáver, sino al propio Marko Ivánovich, escondido, profundamente dormido y borracho perdido.

La "cerilla sueca" se convierte así en ese detalle trivial que derrumba toda una arquitectura dramática construida sobre la vanidad y la incompetencia. La explicación es ridículamente simple: Klyauzov, en un estado de borrachera épica, armó una pelea, tiró todo, se cortó sin querer y, para seguir durmiendo sin que lo molestaran, se refugió en el único lugar que se le ocurrió, el velador. Toda la investigación, con sus sospechas y acusaciones, fue un absurdo ejercicio de autoengaño.

Este final le permite a Chéjov ejercer una crítica social y psicológica profundamente humorística. Se burla con cariño de la pomposidad de la autoridad, de esos personajes que prefieren mil teorías elaboradas antes que admitir la evidencia de la simpleza humana. Dukovski no busca la verdad; busca una historia emocionante que confirme su propia inteligencia. Chéjov nos muestra cómo el aburrimiento y la vanidad suelen ser el motor de nuestras mayores tonterías. Y al final, el cuento refleja ese pesimismo benevolente que tenía hacia la condición humana, nuestros dramas más aparatosos suelen tener raíces banales y patéticas, como la embriaguez o la pereza.

"La cerilla sueca" es, en definitiva, una obra magistral que condensa todo el arte narrativo de Chéjov. A través de la parodia, la economía de recursos, el detalle revelador y una objetividad que hiere más que cualquier juicio, el autor nos revela una verdad universal, a humanidad a menudo se equivoca no por malicia, sino por una ciega arrogancia que le impide ver lo que tiene delante de las narices. La verdad, nos dice Chéjov, no siempre está oculta en las sombras; a veces, está escondida a plena luz, esperando a que alguien, por pura necesidad cotidiana como encender un cigarro, la encuentre.

Soy Médico Microbióloga, amante de la naturaleza, las letras, la música, la cocina y la vida en sí. Férrea defensora de la familia y los niños

Los textos son creados por mi, sin uso de IA

Banners creados en Adobe Fireworks por cortesía de @azufrecs

Gracias por entrar a mi blog

Las fotos son de mi propiedad

Es que te fuiste para el Maestro del cuento ruso!

Bravo por ti

Es verdad, es un maestro, El Maestro.

Gracias por andar por aquí.

Saludos @abelarte.

Niña, oro molido llevas en tus manos 🙏🏻

Thank you! I had convinced myself that I read everything Chekhov wrote, and the idea was a little discouraging. I thought,if I want to read Chekhov--and I do love Chekhov--I must reread him. But now, I think you have offered me a book I haven't read. Maybe I have and don't remember--which is as good as not having read it at all. It will still offer the sense of being 'new'.

This sounds delightful, @camelia28! I was struck by one line you write:

It reminded me of Kafka, where so much of what occurs in a story occurs because people convince themselves of a truth.

I know what I will read this week... Great review.

Hello, greetings.

I'm so glad that while browsing my blog you realized there is still more of the great Chekhov to read.

And yes @agmoore, many people get more and more entangled in their own story; there are many Inspector Dukovskys out there.

You mentioned Kafka, you're right—he said that, and he was very right.

Let's read! Reading is always a good option, and even better if it's by the master Chekhov.

Have a beautiful day.